From an historical perspective, the story of Chint Singh highlights the role of Indian soldiers in the WW2 against Japan and their experiences following the fall of Singapore in 1942. Although the stories of internment in Changi prison are well known, the treatment of Indian POWs by the Japanese in other camps has been largely overlooked.

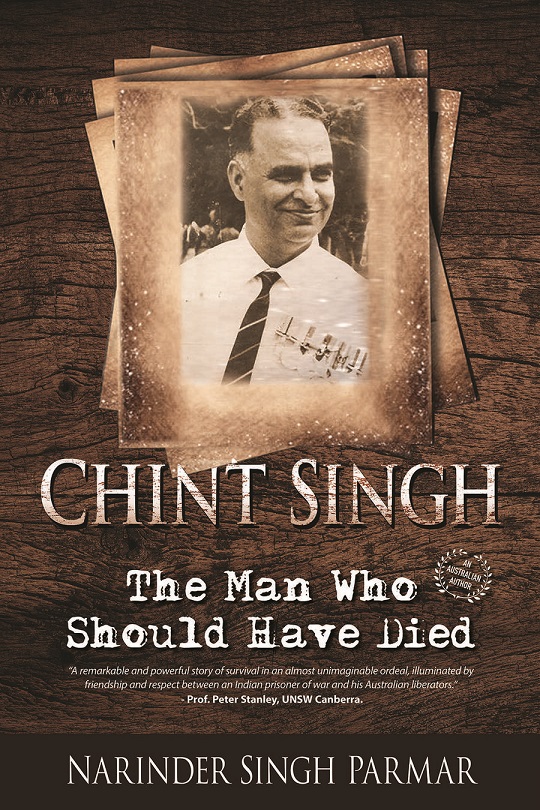

As Chint Singh’s son, I was able to draw upon his personal diaries and his own accounts complied after returning to India at the conclusion of the WW2. Unfortunately, Chint Singh passed away in 1983 before completing his life’s story. I have also been fortunate to receive assistance and guidance from prominent Australian historian, Professor Peter Stanley. According to Professor Stanley this book is “a remarkable and powerful story of survival in an unimaginable ordeal, illuminated by friendship and respect between an Indian prisoner of war and his Australian liberators.”

The book has 12 chapters. In an ‘Introduction’ by the author, gives an account of Chint Singh’s early life, recruitment into British Indian Army and his overseas deployment. After the introduction, the author ‘brings in’ Chint Singh to narrate his own story to the reader.

The content of each chapter is narrated by Chint Singh. In Chapters 2 – 5, he recalls his experience as a POW of Japan. He details harrowing accounts of starvation, over-work and horrific violence at the hands of his captors.

In chapter 6, Chint Singh narrates how he and his 10 comrades were rescued by Australian forces. In his unpublished memoir, Lt F.O. Monk recalls his visit to Chint Singh and his men at Angoram. He wrote: ‘Ten of these poor fellows were lined up in two ranks, some were sitting because of the sores on their feet or their condition generally was such that they could not stand, but all were rigidly at attention… In charge was a smart looking man, Jemadar Chint Singh, also in rags but with most military bearing, who marched up, saluted and said ‘Sir, one officer, two NCOs and eight other ranks reporting for whatever duty the King and the Australian army requires of us’. I found it very hard to reply him.”

Chapter 8 and 9 then provide an account of Chint Singh’s role as chief witness in the Australian War crime commission. In Chapter 10, ‘Journey back home’, Chint Singh shares his observations about everyday Australian life from the horse races to the pub.

Chapter 11 details his role in the case against Lt. General Adachi in 1947. The final chapter recounts his return visit to Australia in 1970. He was invited by the Australian government as Indian representative to mark the 25th Anniversary of Japanese surrender celebrations at Wewak.

The book portrays Chint Singh as a man who believed in the values of hard work, courage, justice and resilience. His leadership qualities, worldly experience and suffering in the World War 2 made him a remarkable figure who earned the respect of many Australians.

As an author, I very strongly believe that this book will promote a new appreciation among the readers of the role of Indian soldiers in the WW2. It will not only help to understand their suffering as POWs but also the courage and sense of loyalty and mateship.