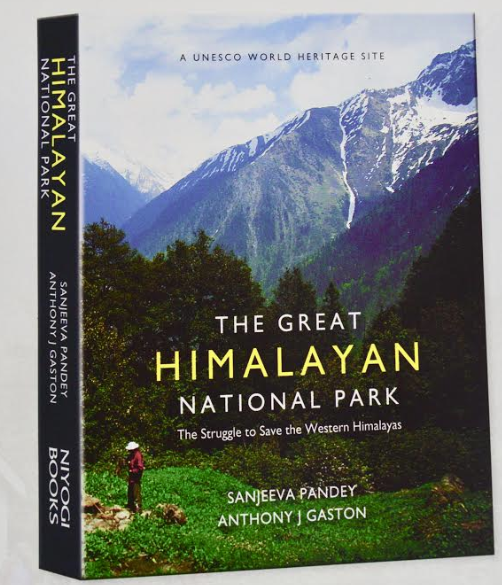

THE GREAT HIMALAYAN NATIONAL PARK- The Struggle to save the western Himalayas.

by Sanjeeva Pandey and Anthony J Gaston.

Published by Niyogi Books, Delhi, 2019. Rs. 1500/. 364 pages.

This book is a long due but worthy tribute to one of the finest ecological treasures in the Western Himalayas, a UNESCO site since 2014, but still unknown to most of us. That it has been penned by the two persons perhaps most qualified to do so ( Pandey was Director of the Park for almost eight years and Gaston had conducted the surveys which laid the groundwork for the Park’s creation) imbues it with an authenticity and insights an outsider would have found difficult to impart. The book is not a scholarly tome, nor a critique of govt. policies, nor a guide, though it has elements of all three, but an introduction to various facets of the GHNP, inviting the reader to go there and find out more for himself.

It begins by placing the GHNP in its natural setting in the north-western Himalayas, detailing its geography, vegetation, climate, forest types, rivers, flora, fauna. Of particular interest is the history, since British times, of issues relevant even today- the effects of grazing and forestry practices, including timber extraction, and the surprising but welcome conclusion the authors arrive at, viz., that” the extent of forest cover, at least in the temperate zone of the western Himalayas, has changed only moderately in the last 100 years.” Those who have visited Manali would find this nugget interesting too: the stately deodars that enfold this town today were all planted by the then Conservator of Forests, one Duff, in the 1880’s- the original stands of pure deodars in the upper Beas valley had all disappeared by then. Never before have so many hoteliers owed so much to one man!

The creation/ notification of GHNP in May 1999 followed a detailed scientific study of the biodiversity and demographics involved. The area of the Park, almost 700 sq.kms was well chosen in the middle and upper reaches of the Jiwa Nal, Sainj and Tirthan valleys. It had a very sparse population, no road connectivity, was well insulated from the “development” activities of the Beas basin and was a rich repository of western Himalayan flora and fauna. Even though no displacement of any populations took place, modifications had to be made to the original plan as the Park took shape: three villages intruded into the Park and they had to be segregated into a separate, 90 sq. km. wild life sanctuary called the Sainj Wildlife Sanctuary; an Eco-zone of 230 sq.kms.was carved out on the western boundaries in 1994 to provide a buffer and absorb the biotic pressures generated by the surrounding villages- grazing, herding of livestock, collection of fodder and firewood, extraction of herbs. The ecozone has 160 villages with a population of 14000 and about a thousand households had been traditionally dependent on the park area for these needs.

The GHNP management quickly realised that biodiversity conservation within the Park would not be possible without providing alternate livelihood options to the families whose rights had been terminated. A Biodiversity Conservation Society was set up in 1996, along with Women’s Self-help Groups and Credit and Savings Groups. Their members were given training and marketing support in vermi composting, propagation of medicinal plants ( which the Forest deptt. buys back), manufacture of handicrafts, jams and pickles and souvenirs. Ecotourism and trekking ensures employment to dozens of youth, as does MNREGA. These well thought out interventions seem to be paying off: as Pandey reports from a study carried out in 2011, there has been a significant recovery of vegetation in the alpine meadows as compared to the baseline of 1999, and the population of pheasants and ungulates has also gone up, the earlier resistance by the locals has declined. GHNP is a case study in demonstrating that biodiversity conservation is possible only through socially inclusive programmes and participatory forest management by involving all stakeholders.

The GHNP is a trekker’s paradise and about one thousand of them visit it each year. The chapter on trekking describes the major treks in the valleys of the four rivers that drain the Park: the Parvati, Jiwa nallah, Sainj and Tirthan. The trekking routes, however, are not marked on the accompanying maps, nor are essential details such as altitudes,distances, support services, required permissions provided. Each trek is not very well delineated as it overlaps with others and can leave the first timer a bit confused. The chapter could have been better structured since this is the part of the book that most readers would be attracted to.

This book is a treasure trove of information for the botanist, zoologist, bird watcher and any lover of nature, for the biodiversity of the GHNP is astounding. It supports hundreds of species of the north-western Himalayan wildlife: 8% of its plant species, 21% of birds, 10% of mammals, 7% of reptiles, 9% of reptiles. It is one of the last remaining refuges of many endangered species: the western tragopan, cheer pheasant, snow leopard, Himalayan musk deer, Asiatic black bear, Himalayan tahr and the elusive serow. Birdlife International has classified it as an endemic bird area. The authors have found that the Park contains the best gene pools of walnut, hazelnut and horse chestnut. ( I had taken some saplings of the last named tree for my cottage in Mashobra and today I have six of these majestic lords of the jungle standing tall on my grounds!). One of the secrets of the success of GHNPis that the sheer geography of the Park makes most of it inaccessible- 68% of its area is above 3200 meters. With four major rivers and 1400 streams, all disgorging into the river Beas it is also a priceless storehouse of water.

The GHNP is now the nucleus of a much larger contiguous Protected Area landscape measuring 2854 sq. kms, comprising the wildlife sanctuaries of Tirthan, Sainj, Kanawar and the 710 sq. km. Kheer Ganga National Park embracing the Parvati valley, created in 2012. The state govt. should now work towards designating this entire landscape into a bio-sphere reserve.

In conclusion, this book can be read at two levels: one, as a celebration of the preservation of what the authors term a fragment of the natural history of the Himalayas, as old as the fabled Pandavas, forever lost elsewhere. Second, as a recognition of the role of biodiversity in maintaining eco-systems and in providing eco-system services. Though mostly successful, GHNP is still a work in progress, an experiment that cannot be allowed to fail. It still faces many threats, to which the authors have alluded in passing: hydel projects, tourism, road construction, vehicular pollution. It will need many more persons of the caliber, and with the devotion and passion, of Pandey and Gaston to enshrine it permanently in the magnificent landscape of the western Himalayas.

Himalayas.

| The author retired from the IAS in December 2010. A keen environmentalist and trekker he has published a book on high altitude trekking in the Himachal Himalayas: THE TRAILS LESS TRAVELLED.

His second book- SPECTRE OF CHOOR DHAR is a collection of short stories based in Himachal and was published in July 2019. His third book was released in August 2020: POLYTICKS, DEMOCKRAZY AND MUMBO JUMBO is a compilation of satirical and humorous articles on the state of our nation. His fourth book was published on 6th July 2021. Titled INDIA: THE WASTED YEARS , the book is a chronicle of missed opportunities in the last nine years. Shukla’s fifth book – THE DEPUTY COMMISSIONER’S DOG AND OTHER COLLEAGUES- was released on 12th September 2023. It portrays the lighter side of life in the IAS and in Himachal. He writes for various publications and websites on the environment, governance and social issues. He divides his time between Delhi and his cottage in a small village above Shimla. He blogs at http://avayshukla.blogspot.in/ |