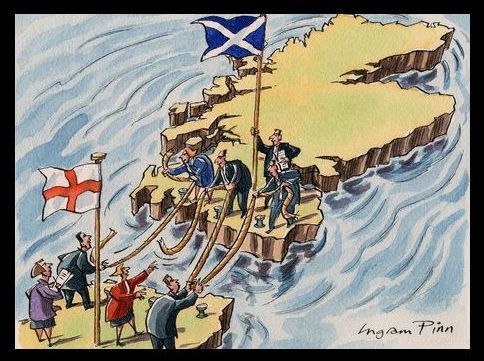

Referendum for Scottish independence drawing closer (18th Sept), questions are being thrown around in the public domain about concerns that this may spell the end for the concept of Great Britain.

While Alex Salmond, the pioneer behind the drive to claim independence for Scotland, refutes such claims as derogatory of the fact that “Britain is as close to a geographical expression, as Scandinavia is. One that won’t go away”, political debate has ensued over the matter, that concerns landscapes either sides of the Pacific.

Britain’s chief problems and one that the queen faces herself is the inherited visage of the nation (England) has been trying to shed, of its imperial yesteryears before the end of the Empire half a century ago. As the Irish, pout and look on with bloated cheeks, Britain stands to lose another working limb.

What is perhaps admirable, and also alarmingly degenerative of the command David Cameron and his team hold over the functioning of the British Isles, is the way in which the referendum has been eased onto his desk.

Cameron has called upon the Queen – who herself awaits the verdict on whether Scotland, if freed, would take her as queen – to convince his fellow islanders on voting against the referendum.

The referendum, itself is a one-of-its-kind charter that would require everyone above the age of 16, currently residing in Scotland to vote against the simple question – “Should Scotland be an independent country?”

The Scottish move for independence is a drab revision of the circumstances the Empire encountered during the uprising of yet another family member, the Irish.

The push for Irish identity, and freedom during the early years of the 21st century marred the idea of ‘Britain’ beyond repair. While the pathos of the time was marked in works by literary stalwarts such as Joyce himself, and theorists that followed him, the same cannot be said about the yet-to-convince Scots.

On one hand, the Irish uprising, coupled with an overbearing search for identity sans ‘generally British’ left an indelible print on life, and literary discourse that ensued in the aftermath of a war that reshaped Europe – not only geographically. As compared – taking into consideration the post-modern etiquette of existence – the Scottish movement has been anything but the same tour de force’.

There have been names, both belonging to literary factions, and otherwise, who have claimed sides opposite the tipping point. Sean Connery, perhaps the most celebrated supporter of independence believes this is an opportunity too good to let go. J K Rowling, author of the famous Harry Potter series thinks otherwise.

A recent survey, suggested that in over a year, since the referendum was first suggested, at least 10 % percent of the Scottish residents have grown to feel “less-Scottish”. The facts, and educated opinion suggests, Britian would avoid a landmark sway in belief, as it failed to do during the Irish war for Independence.

The glib mark of another mutilation aside, there are consequences both parties need to take into account. There is the economic hangover of choosing a currency – Will Scotland keep the pound? Will they adopt the Euro?

There is also the added baggage of UK’s national debt, something Scotland will be set to inherit (between £100bn and £130bn). The UK will have to consider withdrawing from its naval stations from Scotland’s ports – at least by the 2020, Salmond says.

Whatever the verdict of the referendum come on the day of voting, the occasion cements yet another scar on the nation’s history; a history that Briton’s themselves struggle to shrug or adequately acknowledge as ghosts of their imperial past continue to resurface as harvest of the proverbial “as you sow” – from over international borders in America, Africa, Asia and Oceania.

Manik Sharma reads and writes, and that is about as interesting as he gets.