In a nook off the M.G. Marg, a spiffy tourist hangout in the heart of Gangtok town is a tiny eatery. A ramshackle entry with a rotting plyboard signage leads to clean dining quarters done up in traditional Chinese style, with painted dragons on the walls and laughing Buddha icons on the counter. Miniature paper lamps throw shafts of yellow light on the wooden seats, and soft Buddhist trance music flows from hidden devices.

The eatery serves momos – at least 25 varieties of them – in all imaginable stuffings. There is lamb, pork, bird or bovine within the momo, and a red-hot chilli and garlic dip, “tomato achar” and a white sauce of oil and egg white, beaten to a transparent consistency. The momos are usually accompanied by bowls of Thukpa, a noodle broth cooked with vegetables and meat.

“Our palate has changed. We love spicy food but cooked our way. It is a result of the influence of the mainland for the last 30 years, ever since the state became a part of the Indian Union. North Indian spices have carved a place for themselves in our traditional kitchens,” said Geeta Sharma, a writer and a native of the town.

The post-1975 fondness for spices among the average Sikkimese have lent their broths, noodle and meat dishes layered flavours of ginger, garlic, onions, peppers, cumin and coriander. The essence of Sikkimese food is simplicity and improvisation.

Nepal, Tibet, Bhutan and China dominate the Sikkimese palate, with its improvised noodle, meat and rice dishes that come as a cross between spicy Bengali curries, Chinese exotica and the bland Tibeto-Bhutanese and Nepalese food.

Eateries like House of Bamboo, the Blue Sheep Restaurant and Dragon Restaurant on M.G. Marg promote regional fusion fare on their menu – and the staple international favourites as well. But the intrepid shacks with their traditional tastes score over the fashionable addresses.

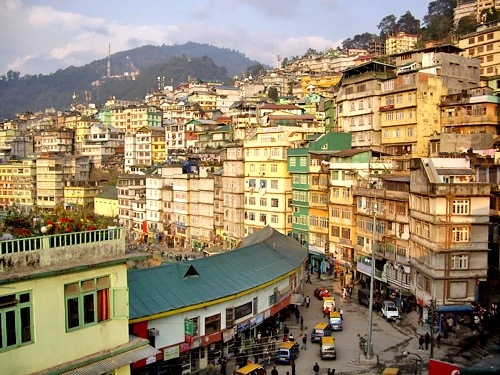

Nestled in the eastern Himalayas, Sikkim with a geographical area of 7,096 square km and population of 600,000 people, straddles the lower slopes under the protective shadow of Mt Kanchenjunga and the Singalila range. With a history that dates to at least the 8th century BC, several ethnic groups find home here, including the Nepalese, Bhutia, Lepcha and Sherpa people.

Sikkim has a tradition of meaty and fermented food and beverages that make for nearly 20 percent of the meals. A combination of breads baked with finger millet, wheat, buckwheat, barley and rice flower – usually fried – is eaten with vegetables, potatoes and soybean.

At the Sikkim International Flower Show 2013 at Saramsa Gardens – the crown pageant on Sikkim’s social roster – on the outskirts of Gangtok, an ethnic food court grabbed the limelight, competing with the colourful orchids.

The all-purpose economy lunch of Nepalese origin “sael roti (concentric rings of rice flour) with “aloo” salad (diced and boiled potatoes, onions and green beans tossed with home-made tomato-chilli sauce, minced peppers and coriander leaves) was a sell-out. It was filling as well.

The “aloo (potato) dum”, as it is known locally, is available in a variety of avatars – potatoes cooked with turmeric, salt and tomato, sauteed potato with chilli dip and tossed with sesame seeds.

One of the more popular and nutritious dishes – often described as the poor man’s protein in the state – is the “kimena” curry, a dish of fermented soybeans cooked with tomatoes, turmeric, green chillies and leafy vegetables and eaten with chambray rice, a local pilaf of Nepalese ancestry and curried mutton that sits easy on palates willing to experiment.

The local liquor, “jaanr” is a pungent brew of fermented millet, maize, barley and cassava roots.

“But we love our cappuccinos, caramel shakes, pizzas and sandwiches,” said Neha Neopanay, a 25-year-old event manager in Gangtok, who chills out at the “hideously expensive” Cafe Coffee Day lounges in Gangtok.

“The coffees here cost much more than elsewhere in the country for some strange reason,” she said. But that does not stop her. She is one of the growing tribe of Sikkimese girls who “lives independently and earns her livelihood”.

“Traditional society is disintegrating. The stress of mainstream cultures is changing some things forever, including food, clothes and traditional ways of life. Some may be lost forever…,” muses Udai Chandra Rai, Gangtok-based counsellor and social worker.

–IANS