Competitive communalism, which in fact, means rivalry between different groups that define their identity primarily along religious lines is like a tinder-box in a country like India that prides itself on its religious and cultural diversity. It has the ominous power to disrupt communal harmony and spur inter-community violence even in a peaceful state like Himachal Pradesh making a mockery of secularism. Not only this, behind the veneer of religious intolerance, lie a bigger malaise of greediness of the Corporate Houses who surreptitiously want to grab the lands where the tribal have been enjoying traditional rights since decades. In this paper an attempt has been made to lay bare the nefarious designs of the communal forces and their cohorts – the Big Sharks who are clandestinely destroying peace to promote their selfish interests.

Petty politics, laced with communal hatred, bigotry and untruth, has been, of late, repeatedly spurring violence even in a peaceful and tolerant Western Himalayan State of Himachal Pradesh. The same simple and hardworking pahari people, who had always remained distant from divisive politics and celebrated their Pahadiness or Himachaliyat for decades since its formation, are now giving in to communal divide. In the month of June this year, a video clip went viral overnight on social media claiming construction of a Majar/Masjid in a forest region in Kumarsain area of District Shimla, Himachal Pradesh. This rumour struck chord with some communal Hindu organizations and they instantly tried to spread the venom of hate among local people of the region. The Divisional Forest Officer, Kotgarh Division had to issue a press note for clarifying the situation and more significantly to calm the tempers. Contrary to the claims made in the viral WhatsApp message, the Official concerned affirmed that no such construction activity had been carried out in the area. It was an unfortunate incident misapprehended by some miscreants who were out rightly trying to disturb communal and social harmony between communities. At the same time another incident of communal violence occurred in Himachal Pradesh’s Chamba, a district located far away from Shimla. Chamba was convulsed by clashes over allegations levelled on a Muslim family having killed a Hindu boy — just a month before the valley’s famous “Minjar Mela” which, ironically, celebrates communal harmony (Chauhan 2023).

Van Gujjar community, which was purportedly alleged to have been constructing the Majar, is, in fact, a peaceful, forest dwelling nomadic tribe that embarks on an epic journey from the lower plains at the onset of spring season to find best pastures for their buffaloes, and unfailingly reach the forest areas of Narkanda (a famous tourist place near Shimla) and Baaggi (famous for apple orchards) in the summer months. Life for this community is all about survival and perpetual movement, meaning thereby, that they migrate only temporarily, with the sole intent to graze their cattle. In compliance to national grazing policy and the directions issued by the State level grazing advisory committee of HP, the forest department has been issuing grazing permits to them for the last so many years. Permissions granted by the state government theretofore vest them only with the grazing rights, and they are forbidden from raising any type of permanent structure.

The Forest Rights Act which was passed by the Parliament of India in 2006, but came into force on January 1, 2008, recognizes the rights of the Scheduled Tribes and other traditional forest dwellers (communities dependent) on forest land of any description (including Under marketed Protected Forests, Demarcated Protected Forests, Reserved Forests, Shamlaat, Charagah, Wasteland, Sanctuaries, National Parks etc) for their ‘bonafide livelihood.’ They have been vested with individual rights, community rights (as grazing and fishing) and development rights that can be claimed by them through the provisions given in the act.

Understanding the Origin of Gujjars

Originally from Jammu and Kashmir the nomadic tribe has overtime spread out across the ranges of Uttarakhand and Himachal Pradesh; it also has a sizeable population living in Punjab, Uttar Pradesh and western Rajasthan too. Various views advanced by historians regarding their origin are contested in literary circles, but the most referred to argument is that in the early 6th Century A.D. a great invasion by Central Asiatic people, who were supposedly Gujjars, took place in the present day western Rajasthan and Punjab. They initially made the new lands their home and later migrated to other parts of the sub-continent. The word ‘Gujjar’ derived from ‘ Gurujar’, which in Sanskrit means ‘a valiant out to crush the enemies,’ finds mention for the first time in Harshacharita, a book written in the 7th century AD by the famous poet Bana Bhatta. With the constant usage of the word, Gurujar got deformed into Gojjar and then to Gujjar (Crook 1974). Since ages, their lives have centred around caring for and searching rich forests and meadows to find fodder for their livestock. They have been eking out livelihood through sale of milk and milk products, and this also serves as a major source of income for many of them even now (Cunninghem 1891).

Regarding their ethnic affinities Denzil Ibbetson (1974) writes that Jats, Gujjars and Ahirs are all of the same ethnic group and he traces a close relationship between all of them. So far as the Gujjars of Himachal Pradesh are concerned, they are presently divided into mainly two groups; firstly, the Gujjar Hindus who are found mostly in Mandi, Kangra, Sirmaur, Solan and Bilaspur districts, and secondly, the Muslim Gujjars who are dispersed in the districts of Chamba, Mandi, Bilaspur, Shimla, Solan and Sirmaur; thirdly, a miniscule section has espoused other faiths due to reasons which cannot be established. Talking about their language, Smith opines that the Gujjars have a distinct language of their own, called Gojri, which varies from place to place but is closely related to various dialects of Rajasthani (Smith 1967). There is no separate script of the language. But in respect to the western Himalayas, the areas of Himachal Pradesh and Jammu and Kashmir they live in, the Gojri they speak is closely related to the Western Pahari set of languages and many include their version of Gojri in western Pahari.

Migration and Settlement of Gujjars in Himachal Pradesh

It is extremely difficult to trace the route, the nomadic Gujjar tribe, may have followed in the early stages of migration to Himachal and then concentrating in some of the areas. But what may have tantalized them into undertaking arduous journey across high plains to picturesque Himalayan valleys is surely the lure of fodder they required for their livestock. T.S. Negi argues that, the Hindu Gujjars made isolated and stray migrations to Himachal Pradesh from the neighbouring plains. The Muslim Gujjars seem mainly to have first set foot in the then princely states of Chamba and Sirmour, and thence spread out gradually to other areas outside these States. Some of them found their way to Kangra district and to erstwhile Bilaspur princely state from the adjoining plains of the British India. To the Chamba princely state, the Muslim Gujjars were driven by the growing inadequacy of grazing resources in the neighbouring parts of the Jammu and Kashmir State (Drew 1976).

Besides scholarly works, a popular and interesting folklore also details how the Mohammedan Gujjars were drawn to Sirmour at the request of the then ruler of Sirmaur, Raja Shamsher Prakash who had visited Punchh for a matrimonial alliance. Abundance of milk and its rich taste made him feel as if it were a land of milk and he craved for a repeat of this possibility in his State. Thereupon, he came to know about the Gujjars and their proud possession, the herd of buffaloes that they valued more than their lives. He requested the Ruler of Punchh to send some Gujjar families to Sirmour and promised to afford them liberal grazing facilities. About nineteen Gujjar families were sent to Sirmour by the King as a part of matrimonial courtesies he was to extend to the ruling family of Sirmour. The Gujjars also exulted at the prospect of getting lush green pastures with plenty of fodder for their livestock at the new place. It is from Sirmour that the Gujjars further migrated to other areas known in those days as Shimla Hill States. There are three main directions and routes of Gujjar’s induction into Himachal Pradesh; namely, from Jammu and Kashmir to Chamba, from Punchh to Sirmaur , and from Kangra and Bilaspur to the neighbouring districts of British India, other than numerous stray infiltrations that went over generations (Crook 1974). At present Gujjar population is scattered almost in every district of Himachal Pradesh. The socio-religious dichotomy between the Hindu Gujjars, found mainly in Mandi, Bilaspur, Solan and Una, and the Muslim Gujjars, found mainly in Chamba, Kangra, Shimla and Sirmour in Himachal Pradesh , becomes explicitly clear from the life style they follow and the religion they profess. It is notable that almost all the Hindu Gujjars of Himachal Pradesh are settled in their permanent habitats and have taken to agriculture and other professions; whereas, the Muslims Gujjars are still stuck to their nomadic pastoral life, though some of them are now settled or semi settled (Smith 1908). The Muslim Gujjars moving with the herd of buffaloes from the high hills to low lands during winter months and vice versa during the summer months present a spectacular sight. Sincere efforts are being made by the Government and various NGO’s to make them a part of the mainstream, but they still have a long way to go.

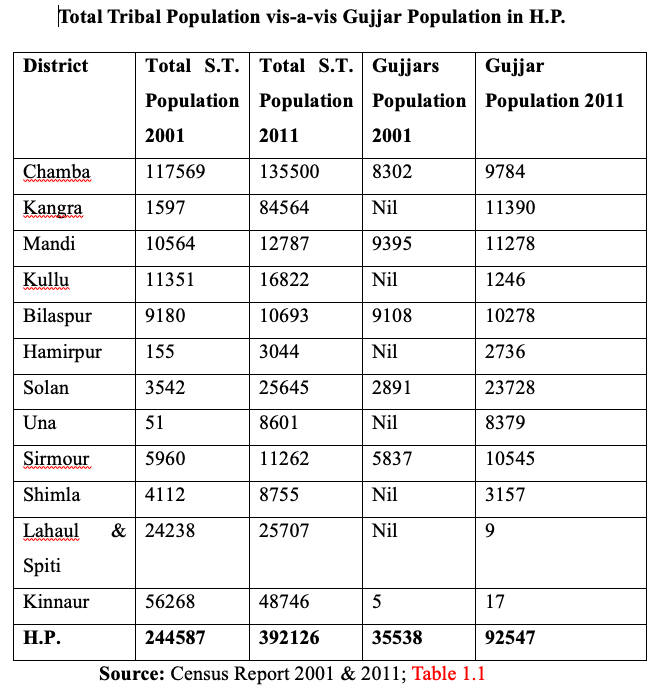

As per Census report 2001, the total population of Gujjars in Himachal Pradesh was 35538, and it reached 92,547 as per Census report 2011. When the total tribal population in the state, which was 3,92,126 in 2011, is taken into account, the percentage of Gujjar population turns out to be 23.60 per cent in r/o the total tribal population. Following table shows district wise Gujjar population and the total tribal population for each district in Himachal Pradesh in the years 2001 and 2011.

The table given above shows that the population of Gujjars registered an increase during 20001 to 2011 and it reached 92,547 in 2011. The main reason behind this increase is that the Ministry of Tribal Affairs, Government of India notified Gaddis and Gujjars residing in merged areas (1966) of the state also as Scheduled Tribes in 2003, and the Gujjar and Gaddi population from these areas was also considered in the Census report 2011.

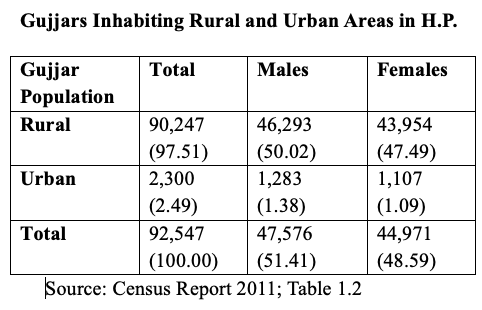

According to Census report 2011, a majority of Gujjars live in rural areas and very few, rather a negligible section of their population, lives in urban areas as shown in the following table.

The table 1.2 shows that 97.51 per cent gujjars in r/o the total population are living in rural areas and only 2.48 per cent are living in urban areas. Furthermore, out of the 97.51 per cent of the rural population of the Gujjars, 50.02 percent are males and 47.49 are females, whereas, out of 2.48 percent of the urban population, 1.38 percent are males and 1.09 percent are females.

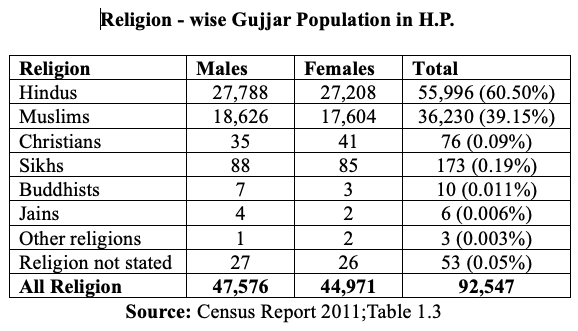

In Himachal Pradesh, a major percentage of Gujjars is that of the Hindus, followed by the Muslims, and a negligible section of the Gujjar population belongs to some other religions. Following table shows data of religion wise Gujjar population in Himachal Pradesh.

It can be inferred from the table 1.3 that different religious beliefs are prevalent among the members of the Gujjars tribe of Himachal Pradesh. The Hindus outnumber the Muslims and the followers of other beliefs are almost negligible. Their different religious beliefs affect their social structure as well as their intra-tribal social set-up, interaction, integration and identity. They live in rural and backward areas, which are generally remote areas of the jungle, and it keeps these people shut out from the modern and urban values. Their nomadic habitat has become a hindrance in the process of their overall development and advancement as they have not been able to utilize the opportunities provided by the Government for their welfare and for protecting their interests. [i]

Physique

The Hindu Gujjars of Himachal Pradesh trace their ancestry from Yashoda, the mother of Lord Krishna, and look like most other Hindus, whereas the Muslim Gujjars, who are a fine race of healthy men with attractive features, expression-less faces and large prominent teeth easily betray their distinct ethnicity. They are tall and gaunt; large and round-headed; of oblong facial profile; with fore-head and chin narrow and a long and narrow nose slightly curved. The aged among them betray the rough and tumble of life in their sun-tanned and puckered physique and their looks rugged looks bear testimony to the storms they have weathered. The youngsters have ruddy whitish complexion and are a picture of robust health. The women too are tall, well-grown, soft and gentle in manner with a shy and modest demeanour, which is indeed captivating. More open and frank in manner than the males, they would not tolerate exploitation and often are known to act independently of social taboos (Russel 1975). It be said in their favour that they hold the marital ties in high regard notwithstanding the suggestion of Barnes to the contrary.In anthropological context they show a preponderance of gene B (26.28%) over gene A (16%) in the ABO system. In the Rh system, they exhibit a predominantly R1 haplotype (56%) with a relatively high prevalence of (25%) like many sub-Himalayan tribal communities. They have a high frequency of gene M and HP2 (81%) in the respective marker systems and exhibit a higher incidence (42.5%) of non-tasters of PTC and a low percentage (2.5%) of G-6PD deficient (Ibbeston & Mechlagan 1914-19).

Livelihood and Family

Barring a few individuals, most of the Hindu Gujjars in Himachal Pradesh lead a settled life, earning livelihood by way of agriculture or other occupations followed in a civilized society; while the Muslim Gujjars are either nomads, semi-nomads or settled. The nomadic Gujjars, be they Hindus or Muslims, remain isolated from the mainstream basking in the glory of their own traditional cultural identity. As mentioned before they remain on the move, along with their herds of buffaloes, in search of fodder for their livestock. They sell milk or milk products, and knowing that the amount of milk produced by the cows and the flavour of the milk is determined by what they eat, the herders themselves collect the best variety of leaves from the forests they pass through. As a majority of them are pastoral, they do not have patron-client, landlord-tenant and cultivator-labor relationship. Also, many have inheritance or warisi in the grazing rights of certain pastures and forests (Majid 1985). Many Gujjars who are semi=nomads or have settled down are still keen on rearing buffaloes as their main family occupation.

The family life of Gujjars is very simple. Amongst the Gujjars the joint family system is the norm, however, nuclear family is also prevalent. In the joint family of the Gujjars, the eldest male number is the head of the family, who is called ‘Sayana’ (Nesfield 1969).All the married brothers and sons along with their families and unmarried brothers and sons of ‘Sayana’ have a common kitchen or ‘Chullah’. All the animals and buffaloes are the common property of the family. The work in the joint family is shared by all the members according to each one’s capacity and capability. After the death of the head of the joint family, the family members may live together in a joint family or may even split to head and manage their own respective nuclear family. There are no hard and fast rules about this. Wherever a Gujjar joint family splits, the separate household, which is also called ‘tabbar’ has its own property in the form of some heads of buffaloes. The head of the split nuclear family is again the eldest male member and in the event of an adult male member not surviving an adult and aged woman acts as the head of the family. In the separated nuclear family, as mentioned above, the eldest male member becomes the head of the family and he enjoys the same line of hierarchal authority for his ‘tabbar’ as did the head of the joint family (Munshi 1955). He is now independent to take decisions regarding the property of the ‘tabbar’ and also enjoys authority in dealings with the community and with the outsiders. It is observed that the main causes of the split of the joint family set-up are usually petty domestic issues like the distribution of work-load among the family members and contribution of income towards family expenses. It may be noted that the major cause of the splitting of the joint family is economic (Saraf 1976). The splitting of the Gujjars joint family set-up due to economic issues shows that the pressure of the modern economy is affecting their social set-up. This is indicative of the gradual pace of social change of the Gujjar tribe towards development and modernization.

Nomadic Gujjars which are mostly Muslims in the state have well-knit social organizations. The first unit of their social organization is the herding unit. In this functional group usually five to six families make one herding unit and they move together to the high altitudes for grazing their buffaloes. During such a grazing expedition a particular herding unit drives its buffaloes as a common unit and shares the fodder in common. After the herding unit Kafila (the convoy) is another functional group, which is also regarded as a unit of social organization. Nomadic Gujjars make a Kafila during the period of migration from high altitudes to the plains before winter sets in. The number of families varies from Kafila to Kafila. After the formation of the Kafila, Gujjars choose their Kafila leader called Buzurg (the elder). Buzurg is the oldest person having knowledge and experience of routes to be followed. He is selected through consensus and once the leader is selected, every member of the Kafila follows the instructions and orders issued by the Buzurg. During migration all the issues and disputes among the families are settled by him with the help of some other senior members of the Kafila.[ii]

Another very important and effective organization among the nomadic Gujjars of Himachal Pradesh is the Dera or a group. The number of families who live together at one place is called the Dera. Every Dera has its own leader called Lambardar. The Lambardar is selected amongst the elders of the Dera through consensus. He not only has to act authoritatively and impartially for the maintenance of social order, betterment and welfare of the group but also as a moral force behind the cohesion of the group for which he is obeyed by all the members of that group. The most important social organization among the nomadic Gujjars is the Biradari Panchayat. Generally, several Deras merge to form a Biradari Panchayat. [iii]The leader or the head of the Biradari Panchayat is called Zaildar and again selected on the basis of his age and his efficiency to work for the welfare of the Biradari and his experience as a group head. In case of a dispute firstly the group tries to settle the disputes. In case a person does not feel satisfied with the decision then the dispute or the issue goes to the Biradari Panchayat. It deals with the cases involving sex, property, and status. The decision of the Biradari Panchayat is final.

Nowadays the institution of the Panchayati raj is working in the tribal areas of the Himachal Pradesh and due to this traditional panchayat has lost its ground in some of the places. However, the nomadic Gujjars who are dispersed over a larger area, still trust their traditional conflict resolution systems. They, being mostly illiterate, shy away from paperwork and seldom trust a system steeped in procedural requirements. However, contradictions are arising within these communities with instances of the people overruling the authority of the Sayanas who heads the traditional panchayat system and are moving towards the adoption of modern legal procedures. Some modern trends are discernible and as a result some of the members of the Gujjar tribe have started reposing faith in the efficacy of modern democratic institutions and statutory institutions of justice. They are beginning to submit their disputes to the Courts of Law and are no longer content with the decisions of their traditional institutions and methods for the settlement of disputes. As a result, they are becoming conscious about their rights which are indicative of their political development and political integration with the mainstream of the society.

Present Conflict

The Indian law defines a forest-dwelling tribe as a Scheduled Tribe and as such all traditional forest dwellers or communities who have resided in forest land for three generations (75 years) prior to 13-12-2005 and who depend on the forest land for their livelihood needs are entitled to claim rights under the Forest Rights Act.

Van Gujjars’ tensions suddenly snowballed in 1983 when the Uttar Pradesh Government spearheaded forest conservation efforts and made its intent to create Rajaji National Park clear, and for the avowed purpose, they were evicted from their winter camps and were allotted lands in the settlements of Pathri and Gaindikatta, near Haridwar (Srivastava 2022). The Gujjars do have privileges and concessions recognized under the Indian Forest Act, 1927 and after Independence under FRA 2006 (Vajpeyi & Rathore 2022). But in Himachal Pradesh, a proper implementation of these Acts is not in sight due to lack of political will and a sense of insecurity that gnaws influential persons who have grabbed common lands in or near forests.Now, a new set of procedures under the Forest (Conservation) Rules, 2022[iv], being pushed by the Central government to replace the Forest Rights Act 2006 are underway However, in September 2022, flagging concerns over the provisions in the new rules that proposes to do away with the consent clause for diversion of forest land for other purposes, the National Commission for Scheduled Tribes (NCST) had recommended that these rules should be put on hold immediately.

Tribals Rights are Essential for Protection of Hills

Tribal population across India shares a similar predicament of being marginalized from the plural majorities surrounding them, and the tribal areas are mainly governed by the constitutional provisions of the ‘Fifth Schedule’. The Indian Republic, in many ways, pioneered a protected regime for the indigenous people, but the moot question which is pertinent to be investigated is to establish the extent to which the protective laws have shielded the tribal population against outside pressure? (Wahi, Bhatia, Shukla, Gandhi, Jain, Chauhan, 2017). It is found that the constitutional provisions promising to safeguard the Land Rights of various tribes work only to a limited extent because they are pitted against a contrary legal regime that strengthens the powers of the state to expropriate land (for purpose of mining, dams, infrastructure etc.). Studies of intra-community land alienation carried out among the Western Himalayan Tribal groups indicate that, in the context of modernization and neo-liberal influences, interplay between formal and informal institutions governing land has weakened the protective nature of tribal communities and enabled elites to privatize large tracts of land. (Wahi 2016) Dominant tribal groups, often, are able to capture most of the benefits to the detriment of smaller or less resourceful tribes. It has been consistently found that numerically, economically and politically more powerful tribal groups are able to corner most of the special benefits.

There is a continuous struggle between constitutional laws under federal structure and pressures from tribal power structures. Contradictions are increasingly creating further conflicts between the State and the communities. However, the indigenous people have helped in conservation of bio-diversity. Efforts for conservation have to be made in both vertical as well as horizontal direction due to rapid industrial revolution. (Navatia and Soereida 2017)

The recent floods and resultant disaster in Himachal Pradesh was termed by many environmentalists and ecologists as man-made. Manshi Asher, who is the co-founder of Himdhara Collective, said “The hills in Himachal Pradesh are very young. They are still under formation and not yet hard.” Asher said “In such a fragile environment, deforestation, road cutting, terracing and change in agriculture crops requiring more intense weather is causing landslides.” In Himachal the hydropower proliferation in the name of “clean energy”, has brought rapid land use changes adversely impacting local terrestrial ecosystems and communities inhabiting them. The loosened hills cannot take the load of high-intensity rain and thus collapses in the form of landslides. The mining in the state is also increasing the incidents of landslides. Himachal Pradesh Public Works Department (PWD) minister Vikaramadiya Singh blamed alleged illegal mining for the damage caused by the floods along the Beas River in Kullu District. (Kajal 2021)

Gandhian freedom fighter, Sunderlal Bahuguna, an environmentalist of repute, worked tirelessly for a self-sustaining ecological model which was most suitable for the mountain state of Uttarakhand. He spearheaded the anti-Tehri dam movement and led Chipko movement aimed at protection and regeneration of native species of trees. When flash flood devastated Utrakhand in the year 2013, he warned, “It is a man-made disaster. When you try forcefully to change nature and its landscape, it gets back and punishes you. This was a land meant for meditation, but it has been turned into purely a tourist destination. The government and the big private money have brought in changes on a gigantic scale, totally unsuitable and detrimental for fragile ecosystem of the Himalayas. If the government wants to end this cycle of disasters it should ban excavations, big dams, and construction of roads in higher altitude and fragile regions. Dams on free-flowing serpentine rivers are making the living water dead.” Exactly 10 years after the aforementioned flash floods had hit Uttrakhand, Himachal Pradesh has been ravaged by similar flash floods in June 2023. Indisputably, nature has its own ways of stemming the ongoing rot going on recklessly by denuding forests and displacing the inhabitants in the name of development. The pastoral tribes which are labelled as encroachers have always followed the healthy tradition of respecting environment. By instinct they know that their survival depends on the health of the ecosystems and hence they always use resources sustainably. If they are pushed to the corner, their knowledge about each plant growing in and around forest dwellings will also go into oblivion. They live off the land without any amenities and remain grateful for what they have.

The Way Forward

The present conflict is the outcome of an unhealthy nexus between Big Sharks and communal forces trying to give to every small incident a communal colourthus eating the vitals of the very social fabric of our diverse society. Himachal Pradesh has been a peaceful, riot-free, and harmonious state since its creation after independence. But as they say, nothing is perfect, Himachal Pradesh is high on the radar of some religious fundamentalists who are trying to disturb the religious harmony of the state and targeting the peace-loving Himachalis. This kind of hate mongering, if allowed to go unchecked, will trigger inter- community violence in the State.

Secondly, it is a part of some nefarious design being laid by the local as well as national corporate or Big Sharks involved in illegal mining near the river banks and running flourishing unsustainable tourism industry in the hills. Forest land is required by them for their projects, and hence, through power and pelf they have been making consistent efforts to get the existing laws changed which had earlier been protecting traditional rights of these tribal communities. The existing development model for the hills must be revisited for making it viable and sustainable as Sundarlal Bahuguna had cautioned in 2013. After Uttrakhand disaster, Kinnaur district of Himachal has been a witness to bone-chilling impact of unplanned power projects which had come up by disturbing the whole ecology of the region. This is the year 2023 and the monsoon fury does not seem to be abating and the pictures of devastation are a common sight. Gandhian Model of development based on small scale industries, which is eco-friendly and more sustainable, could be the solution. Small Home Stays, Micro Hydel Projects, Co-operative Farming and home-made fruits products and other SMSEs are viable solutions for sustainable development in Hill States.

Thirdly, Himachal Pradesh is a virtual kaleidoscope of different tribes with different lifestyles, customs and religions, each complete in itself. The inter-community clashes in the recent past have surely been the handiwork of some fundamentalist organisations. The Gujjars are an integral part of society and have been fulfilling the economic demands of the locals since decades. Sadly, some miscreants are unnecessarily creating a wedge between the communities which have always been above boundaries based on religion. But on a positive note bigots and the corporates would not thrive, only Himachaliyat will win. Let us save the Gujjars from becoming a mere speck in history.

References

Chauhan, Saurabh, (2023), Himachal’s Chamba Tense after Muslim Family Allegedly Kills Hindu Boy Over Affair. The Print, 16 June. https://theprint.in/india/himachals-chamba-tense-after-muslim-family-allegedly-kills-hindu-boy-over-affair/1628884/

Crooke, W (1974). The Tribes and Castes of the North-Western India, Vol.II. Delhi: Cosmos Publication. p.440.

Cunninghem, Alaxander (1891). Archeoloqical Reports II, New Delhi: Director General, Archaeological Survey of India. p. 61

Denzil, Ibbetsoni (1974). Punjab Castes. Delhi : Publishing Corporation. p.185.

Drew, Frederic (1976). Jamoo and Kashmir Territories a Geological Account. Delhi: Cosmo Publication. p.109.

Hussain, Majid, (1998). Geography of Jammu and Kashmir, New Delhi: Rajesh Publications.

Ibbetson, D. & Machlagan Rose, H.A. (1911), A Glossary of the Tribes and Castes of the Punjab and NWFP. Lahore: Printed by the superintendent, Government Printing, Punjab

Kajal, Kapil (2021). In Himachal Pradesh Climate Change and Unplanned Development are Causing Disasters. In Himachal Pradesh, climate change and unplanned development are paving the way for disasters (scroll.in)

Munshi, K.M.(1955). Glory That was Gurjaradesa (A.D. 550-1300), Gujrat: Bharatiya Vidya Bhavan, 1955.

Navatia, Shrivastava and Soreide, Kavita Navlani (2017). Tribal Representation and Local Land Governance in India: A Case Study from the Khasi Hills of Meghalaya. CMI Working Paper WP 2017:4/26p Tribal representation & local land governance in India: A case study from the Khasi Hills of Meghalaya CMI Working Paper number 4 (researchgate.net)

Nesfield, John, C. (1969) Brief View of the Caste System of the North-western Provinces & Oudh, Reprint Delhi, 1969.

Russel, R.V. (1975). The Tribes and Castes of the Central Provinces of India, Vol. III, Reprint. London: Macmillan & Co., Ltd.,

Saraf, Suraj (1976). ‘Gujjar-Nomadic Life, Rich Heritage’, The Sunday Tribune, January 11, 1976.

Smith, V.A. (1967). The Early History of India. London: Oxford University Press. p.427.

Srivastava, Raghav (2022). ‘The Making of Pastoralism: An account of the Gaddis and Van Gujjars in the Indian Himalaya.’ Research, Policy and Practice, Vol. 12, No. 42. https://pastoralismjournal.springeropen.com/articles/10.1186/s13570-022-00259-z

Vajpeyi, Aditi and Rathore, Vaishnavi (2022). “Forest Rights Act in Kinnaur, Himachal Pradesh A Bureaucratic Unmaking.” Economic & Political Weekly. Vol lV, No 4, January 25, 2020. http://www.himdhara.org/wp-content/uploads/2020/03/CM_LV_4_250120_Aditi-Vajpeyi.pdf

Wahi, Namita (2021). How Singur Turned the Tide on Land Acquisition in India. The Wire, 28 September. How Singur Turned the Tide on Land Acquisition in India (thewire.in) .

Wahi, Namita, Bhatia, Ankit, Shukla, Pallavi, Gandhi, Dhruva, Jain, Shubham, Chauhan, Upasana (2017). Land Acquisition in India: A Review of Supreme Court Cases (1950-2016). Centre for Policy Research. February 27.

Notes

[i] The various data relating to the 1911, 1921, 1931, 1961, 1971 and 1981 Census cited here before has been reproduced from the relevant Census documents published under the authority of the Government of India. Special Table for Scheduled Tribes for Himachal Pradesh, 1991 Census, is yet to be published.

[ii] Punjab Govt. Gazetteer on the Kangra District, Pt. I; 1883-84; Lahore.

[iii] Barnes George C., Report on the Kangra Settlement, 1850-52; Lahore, 1855.

[iv] New Forest Conservation Rules, 2022, https://pib.gov.in/PressReleasePage.aspx?PRID=1845824

Devender Sharma, PhD, teaches political science to under graduate students at Government College, Sanjauli, Shimla. The institution is affiliated with Himachal Pradesh University.