As we gaze out from Shimla, the majestic beauty of various hilltop mountains—from Shali Peak to Dhauladhar, and from Tara Devi to Kufri Hills—it often captures our collective imagination. These stunning landscapes are part of the larger, immense expanse of the North-Western Himalayas, which looms large in human culture, legends, tales of adventure, and human achievement.

The need to write this article arose from recent disasters that have impacted the state. These events have sparked a renewed interest in Himalayan studies among government bodies, the scientific community, and most importantly, the general public. Consequently, there is a need to bridge the gap between academic understanding and public knowledge.

While diverse sources of information on the Himalayas abound, they often provide an incomplete picture, making the dissemination of accurate knowledge all the more crucial.

This article aims to offer the layman a general understanding of the vast and important aspects of Himalayan geology. Although the subject’s terminology can be daunting, it’s crucial to approach it with precision. As William R. Dickinson aptly stated, ‘Distinguishing between myth and science is subtle, as both seek to understand the world around us.’ This viewpoint helps us avoid the twin pitfalls of dilution and oversimplification

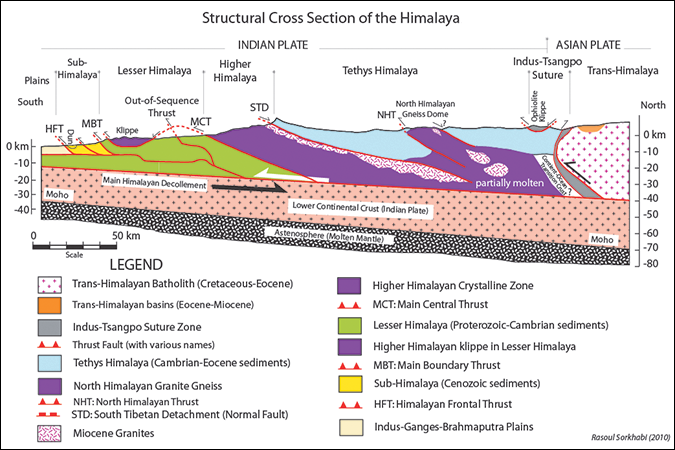

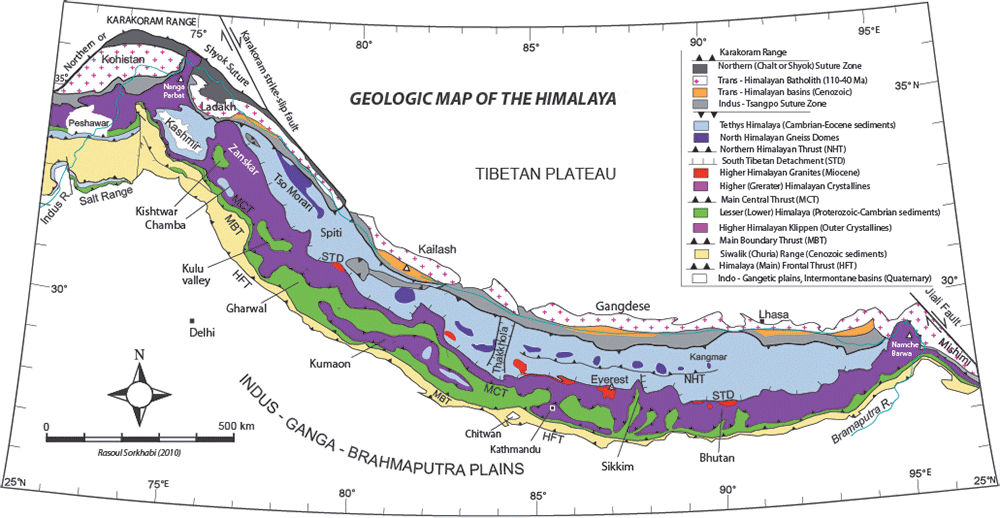

The inspiration for this article comes from the ground-breaking research paper “Cenozoic Tectonic Evolution of the Himalayan Orogen as constrained by along-strike Variation of structural geometry, Exhumation History, and Foreland Sedimentation” by An Yin in 2006. The paper is not just a review, but a revolution in our understanding of the region. Well, the story starts with the process of continental-continental collision (something like a slow-motion car crash) between the Indian and Eurasian plates which started 65 Ma (million years, as we deal with such a large time scale range!) and leads to the closure of Tethys sea, this collision over such vast time/ still working created the world’s youngest Mountain chain.

Thus it is very important to understand the complex geological narratives that are built over 150 years of research.

So to understand the complex geology of North-Western Himachal Himalaya, let’s embark on a road journey from Chandigarh to Kaza, as it serves as an excellent gateway to understanding Himalayan geology.

Starting our journey in Chandigarh, we find ourselves in a foreland basin, characterized by a U-shaped depression filled with alluvial plains. These plains are shaped by the material transported by rivers over time. As we ascend the elevations, we cross the Himalayan Frontal Thrust (HFT), a significant thrust or reverse fault where the hanging wall moves upward or places older material on top of younger strata.

Upon leaving the HFT behind, we enter the Shiwalik Hills. Composed mostly of mud and sand-like materials, this region offers prominent places such as Parwanoo and Kalka, which are known for their Cenozoic sequences. Continuing onward, we reach Subathu, Kasauli, and Dagshai. These areas predominantly feature sedimentary rocks; Subathu is particularly noteworthy for its marine rocks, whereas the rest primarily consist of continental rocks, can offer evidence of the early Tethys Ocean between the Indian and Eurasian plates.

As we make our way toward Solan, we cross another significant fault line: the Main Boundary Thrust (MBT). This region is dominated by limestone, often referred to as the Krol and Infra-Krol formations. As we near Kandaghat, black-colored rocks become visible, indicative of Cryogenian rocks that reflect Snowball Earth events from the Proterozoic era.

We then enter the Shimla region, which is surrounded by the Shimla formations. As we approach the city, the geological features transition into high-grade metasedimentary rocks, primarily constituting the Klippe region. This area is part of the Lesser Himalayan Sequence (LHS), with a geological timeline ranging from 1870 to 520 million years ago, extending back to the Proterozoic and Cambrian periods.

Our journey continues as we encounter a variety of rock formations between Narkanda and Rampur. Notably, in Rampur, we observe the Main Central Thrust (MCT-1) and the Berinag Formation, which primarily consists of sedimentary and metamorphic rocks. Beyond Rampur, we traverse through the Jeori and Wangtoo formations, which are mainly igneous and metamorphic rocks up to the Karcham area. Here, we cross the Vaikrita Thrust System, also known as MCT-2, and enter the Greater Himalayan Crystalline Zone. This zone, also known as the Greater Himalayan Crystalline Complex (GHC), has an approximate age range of 1800 to 480 million years, dating from the Paleoproterozoic to the Ordovician periods. This area boasts very high-grade rocks and nearly vertical mountains, such as those in Mount Everest in Nepal. Reckongpeo is situated within this fascinating region. Finally, as we cross the Thopan area, we encounter mesmerizing hot springs.

As we proceed, the metamorphic grade begins to diminish, and we cross another significant geological feature: the South Tibetan Detachment System (STDS). Beyond this point lies the Tethyan Himalayan region, characterized by its wealth of sedimentary and metasedimentary rocks. As we near the Akpa Bridge, we navigate around the Kaurik Changno Normal Fault System. This area is notable for its neotectonic activity, which was responsible for the 1975 Kinnaur earthquake with its epicenter in Kaurik Village.

Subsequently, we cross the Sangam Bridge, where the Spiti and Sutlej rivers converge, and head toward the Nako region. This area is home to Leopargil, the highest peak in Himachal Pradesh. The landscape then unfolds to reveal the idyllic Leo Village, situated on the left bank of the Spiti River. Continuing our journey, we came across the water crossing at Maling Nalla. Known for being prone to landslides, this area serves as a gateway to Chango village. Along the way, we catch glimpses of the Kaurik Changho Fault System, renowned for its Chango apples.

Continuing our journey, we pass through Shalkar and arrive at Sumbdo, where the Spiti and Pare Chu rivers meet. On the right bank of the Spiti River, we find Hurling Village, known for its organic apples. Geologically, from Sumbdo to Kaza, and extending to the Mud area in the Pin Valley, we traverse the Tandi Thaple-Muth-Lipak formations, also known as the Tethyan Himalayan Sequence (THS; 1840 Ma– 40 Ma; Paleoproterozoic to Eocene). These formations are of marine origin and are abundant in marine fossils. Additionally, these regions provide an ideal habitat for sweet green peas and other high-altitude Himalayan flora, set against a backdrop of breathtaking beauty.

This journey serves to create a mental map for the reader, aiding them in correlating geographical and geological features when they traverse or study these regions. The diverse lithologies or sets of rocks describe the immense character and varied processes that have shaped the Himalayas.

As we conclude our geological journey through the Himalayas, we often encounter the question: ‘Are the Himalayas fragile?’ Well, these mountains are neither simply fragile nor solely resilient; they are complex. The region showcases remarkable Geodiversity, from sedimentary formations to high-grade metamorphic rocks. Concurrently, it also hosts an impressive array of biodiversity, featuring everything from high-altitude flora to unique ecosystems. Although the rocks themselves may range from fragile to incredibly hard, the term ‘fragile’ should be applied thoughtfully when discussing the Himalayas as a whole. They represent a blend of both Geodiversity and Biodiversity, each requiring balanced and careful management for sustainable coexistence. This article serves as a roadmap for understanding the complexity of the Himalayas, fostering deeper respect and a more informed approach to this irreplaceable region.

Sources:

- An Yin 2006 Research Paper: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.earscirev.2005.05.004

- For Geological time Scale and ages: https://pubs.usgs.gov/fs/2007/3015/

- For Plate tectonics and continental- continental Collision: https://www.iris.edu/hq/inclass/animation/continental_collision__indiaasia

Shubham Chaudhary is a geologist. He teaches geology to undergraduates at a government college in Himachal Pradesh. He lives in Shimla.

Very useful information 👌 credible , I was geography student lond time ago now lawyer . Thanks sharing credible insight with regard to Himalayas.

It’s a very interesting article. Thank you Shubham Chaudhary.

I am currently reading a book titled “Indica – A deep natural history of Indian subcontinent” by Pranay Lal, in which there are several references to the evolutionary indications in Spiti valley. Now I understand, it was bed of the Tethyan sea earlier and hence, so many marine fossils are found there.

Dr Kummur R M

Bengaluru

I would like to jnvite you for an interview would you be interested

Definitely, we can discuss ([email protected]).

Thanks Mr. Shubham for bringing it all together to let people be aware that we are dealing with a unique and evolving geological system, called, the Himalayas.

The more i rise my head to appreciate the scenery caused by the complex processes of the colliding landmasses, the more respectfully i pass through this dynamic land.

Thanks sir

It is excellent narration of Himalayan geology while traveling towards Shimala and beyond.

Mr Shubham, I am a geologist and ex ONGC person. Please put such type of journey details in public domain for the information of geoscientific community and public.

Thank you

Thank you for your kind words and appreciation, sir. My primary goal in writing about the Himalayas is indeed to make this magnificent and complex geological region more understandable and significant to both the geoscientific community and the general public. I am inspired to know that my efforts resonate with experienced geologists like yourself. Your encouragement motivates me to continue sharing these journey details and insights with a broader audience.

Warm regards,

Shubham

Very interesting trip. What is the difficulty level?

Interesting chronology of geological events told through a road trip. 👏

Leo village is located on the right bank of Spiti river. 🙂

thanks for correction sir

Thank you Shubham Choudhary.

How many of us have driven the routes across the region and failed to understand what we see sround us?

In India, geography is taught as a compulsory subject in secondary schools (class 6 th to class 10 th) affiliated to all of its school boards. The subject is considered as a part of social science, yet many differences can be found in the way it is practiced in schools across the school boards and the quality can be highly variable.

Crucially, the govt report the underqualification of geography teachers is widespread, and in many schools geography is taught by social science teachers who are non-geography graduates.

Please can I have my chance to learn school geography again and have Shubham Choudhary as one of my teachers?

Thanks for appreciation Mam

Simply delighted to read your article