Shimla, the erstwhile capital of British India, is all set to get a much-awaited development plan (the Shimla Development Plan, 2041, as it is known), according to the town and country planning (TCP) department, the agency responsible for preparing it.

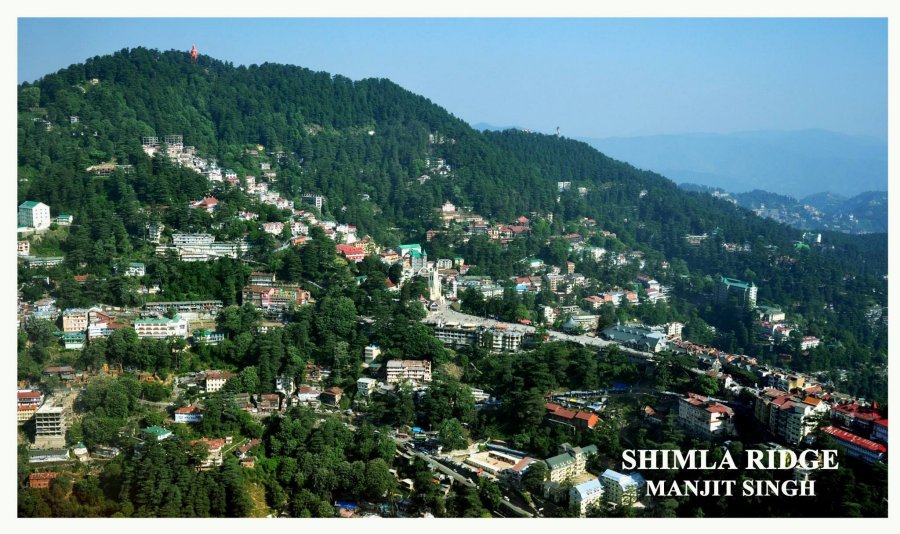

Built by the British in the early 19th century, the town of Shimla had one of the first municipalities in the country, dating back to 1851. Until Independence, the town was guided mostly by British architectural laws with spatial planning limited to a governing capital.

Mostly Gothic, Tudor and Victorian styles of architecture are found in the city which lay great emphasis on pedestrian mobility. The town also had several fire hydrants in different parts and water was supplied both through gravity and pumping since electricity generation started as early as 1886.

After Independence, Shimla was run by several different governments. It was first the capital city of the East Punjab province and, after the formation of the state of Himachal Pradesh in 1971, it became the state capital of the same.

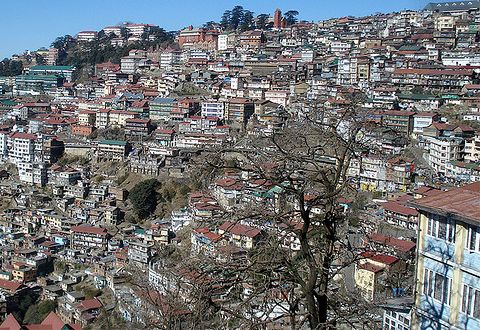

Since 1979, Shimla’s development and spatial planning have been governed by an interim development plan, which has seen lots of tweaks since then to suit the interests of the powerful. The town is divided mainly into three areas: the core, the open and the green belt.

The SDP, 2041, announced a few days back, was supposed to address the problems of the town and its residents, emerging from haphazard planning under the interim plan. However, a cursory look at the SDP shows that these issues have not been addressed in the way they should be while preparing a master plan for a hilly town.

“This is a sheer copy-paste model of the plains with no sight for the hills and the mountains and is a waste of nearly Rs 80 lakh; the amount that was given to the private consultant from Ahmedabad that wrote this draft plan in a period of no less than two years,” said an eminent architect from the town who has been following the developments closely.

A short-sighted, deficient Shimla Development Plan

Instead of creating a typology and vocabulary for spatial planning in mountains, the new SDP falls back on the old designations of areas as core, non-core, sinking, heritage and green belt. This understanding is erroneous since no justification has been provided while deciding which area should fall in which category; the floor-area ratios (FAR) for these categories are different. Moreover, no study has been undertaken to justify the proposed heights of buildings in the areas, which have been suggested arbitrarily.

What the town really needs is a sectoral plan. Unlike the plains, where the surface is flat, hills have varied topographies and rock strengths. Without proper scientific studies of the slopes of the mountains in different directions (north, northwest, south, southeast and so on), a general division of space into the abovementioned categories is arbitrary and unscientific. Paranoia about height should not be the driver for the planning process.

The second major flaw is that while some spaces continue to be considered as ‘green’ areas, dense forests have been left out of green cover. The 17 existing green areas were categorised as such arbitrarily and retrospectively.

The owners pieces of land in the green belt had bought the plots from the municipal corporation, but after categorisation, they were barred from construction activities entirely. The SDP, 2041 provides some relief by allowing the construction of a habitable area, but of only one floor. The patches of greenery, instead, should have been decided to keep in the mind the existing flora on the surface.

As a result, the SDP has turned out to be exclusivist in nature. Neither the TCP department nor the aforementioned private consultant actually interacted with the people of the town to seek their suggestions, resulting in a completely top-down exercise.

While the SDP’s development as a Geographic Information System (GIS)-based plan is a great step towards appropriate and efficient data management, one can only hope that stakeholder consultations and relevant studies to gather data have been carried out by the authorities.

Interestingly, the government, which took two years to prepare the plan along with its team of consultants, has only now sought suggestions from the people and has given them only one month to respond. What’s more, the government has complete veto power with regard to any suggestions. A minimum of six months should have been provided for suggestions to address the issues with the plan.

The draft also contains some overstated figures. For example, the SDP estimates that the population of Shimla will jump from nearly two lakh to six lakh in another 20 years. This goes against the current population growth rate as well as the scope of migration. The much-hyped ‘magnet’/’satellite’ towns are complete non-starters, as they have been in the past and the SDP relies on them too heavily.

The draft is also curiously silent on the mobility aspect, which should have been a point of focus. Shimla has the advantage of being one of the most pedestrianised towns in the country and efforts should be taken to strengthen this aspect and dissuade motorised transport. The plan should also aim at improving public transport and last-mile connectivity.

However, there is nothing concrete in the plan. Even some proposed plans to ease traffic by constructing tunnels across the mountain for pedestrians and motorised mobility have been shelved. The 2014 Shimla Comprehensive Mobility Plan had said that the town should focus on both vertical and horizontal mobility, however, the same cannot be seen in the new draft SDP.

Moreover, there is not a word in the SDP on public housing, rental housing and labour hostels, despite demand for the same. Shimla runs six labour hostels and is thus one of the best towns in the country with respect to providing shelter to unorganised labour. However, all six of these labour hostels were constructed in the British era and not a single addition has been made since then. The 2012-17 municipal corporation had kept a budget aside for the construction of three new labour hostels, however, construction was never taken up.

The SDP also proposes an increase in the FAR for non-core (residential and commercial) as well as core areas. The FAR is the ratio between the total floor area of a building and the size of the piece of land it is built upon and it is important to assess the impact of such decisions on the already-stressed city core and infrastructure.

The city is already choking under the pressure of development and since one of the salient features of the SDP is to decongest and transfer the urbanisation load, such recommendations should be supported by careful review and planning for required infrastructure at the city level, such as electricity, water supply, transportation, parking, sewerage and stormwater and the like.

Further, it will be important to understand how the SDP plans to ensure sustainable development while proposing an increase in construction activity, area under transportation, commercial activity and so on.

Interestingly, despite Shimla’s rich cultural heritage (natural and built) as well as beautiful and significant architectural buildings, areas and precincts, heritage doesn’t seem to be a key aspect of the SDP. The document doesn’t clearly state its approach or the intent towards conservation and protection of the same.

Finally, the SDP fails to address the question of what will happen to the thousands of houses constructed in the merged areas of Shimla town, which are part of the Shimla Planning Area under the Shimla Municipal Corporation. Rather, the draft leaves the question to the government. Infrastructure planning in the town as a whole needs to be done keeping in mind the many buildings here and the thousands of people residing within them.

Overall, the new SDP is an exercise forced by the National Green Tribunal (NGT) and which lacked the governmental and political will which could have made it far better, if the questions of heritage, specific spatial planning for a mountain town and the other aforementioned issues had been considered.

By

Tikender Singh Panwar & Deepika Saxena

Tikender Singh Panwar is the former deputy mayor of Shimla and is currently a senior visiting fellow at the Impact and Policy Research Institute and an advisor to the Samruddha Bharat Foundation.

Deepika Saxena is a conservation architect from the School of Planning and Architecture, New Delhi. She works towards the conservation of built and natural heritage and actively engages with traditional communities for the conservation of knowledge systems.

Former deputy mayor Shimla.

National convenor, NCU, National Coalition for Inclusive & Sustainable Urbanisation.