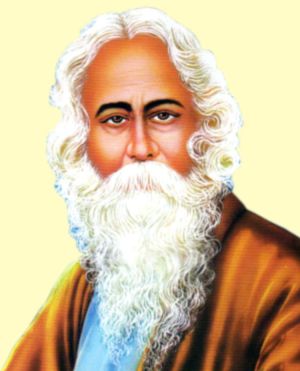

To reconsider the legacy of Rabindranath Tagore (1861-1941) on his 152nd birth anniversary is to confront a maze of contradictions. What, for instance, inspired a school dropout without a college degree to establish an international university? Why did a member of the land-owning ‘zamindar’ class feel compelled to write about the lives of oppressed peasants, and to experiment with schemes for rural development? How could a man write so insightfully about the lives of women? What made him express religious devotion in erotic language, and love in the language of religion? Why did he yearn for fame, yet live in constant fear of it?

Difficult questions, but some clues may be found in the chequered narrative of Rabindranath’s own life. He was born, he tells us, at the confluence of three important movements: the wave of social and religious reform, the literary renaissance in Bengal, and the nationalist struggle. His grandfather, Dwarakanath Tagore, was a well-known entrepreneur, and his father, Debendranath Tagore, was a pioneer of the Brahmo Samaj, a group of liberals who opposed Hindu orthodoxy. The youngest of 14 children, Rabindranath grew up in a privileged household in Kolkata, in an eclectic atmosphere where he was exposed to multiple cultural influences. He could never adapt to formal systems of schooling; he received his real education from the rich cultural environment of his home and family, and his travels in India and abroad. His literary talent blossomed early, and under the influence of his brother, Jyotirindranath, he discovered his gift of music.

In childhood and adolescence, his sister-in-law Kadambari Devi became his playmate, companion and early muse. As a young man, he was sent to East Bengal (then East Pakistan, now Bangladesh) to mind the family estates there. Here he fell in love with the riverine landscape of Bengal, and also developed a strong social conscience, as well as an understanding of psychology, through his direct contact with ordinary people. At 20, he married Mrinalini Devi, aged ten. They had several children, and their marriage was a happy one.

In the early 1900s, Tagore suffered a series of personal losses, with the deaths of his father, his wife, and his favourite child. During this period, he first espoused, and then moved away from, the fiery nationalism of the ‘swadeshi’ (nationalist) movement. In 1913 came the Nobel Prize, and international acclaim. In 1919, he renounced his knighthood in protest against the Jallianwallah Bagh massacre by the British soldiers. All his life, Tagore travelled restlessly, in search of diverse cultural experiences, but also often to raise funds for Visva-Bharati, his university in Santiniketan, West Bengal. Late in life, Tagore emerged as a painter of rare talent. His works drew international attention thanks to the efforts of Victoria Ocampo, an Argentinian woman with whom he formed a close friendship.

Tagore was a complex person, tormented by inner conflicts. He craved for solitude, yet felt a profound sense of affinity with others. He yearned for fame, yet lived in constant fear that it would dilute his genius. Through his long career, Rabindranath was dogged by controversy. Many did not understand his ambivalence about East-West relations, for though he opposed British imperialism, he remained a great admirer of English literature and art. Deploring aggressive and materialistic forms of nationalism, Tagore criticised Japan for aping the West, yet affirmed his faith in the future resurgence of Asia. Though he and Gandhi shared a mutual admiration, they differed on many counts, for Tagore did not endorse the Non-Cooperation Movement, and placed humanism above nationalism.

When he died in 1941, Tagore left behind a staggering body or work. A prolific writer and artist, he composed not only poetry but also plays, stories, novels, essays, songs, satires, travelogues, memoirs and letters. He wrote, for instance, almost 100 short stories, over 40 plays, and more than 2,000 songs. His collected works and letters run into more than 30 volumes. About 3,000 paintings are attributed to him. His doodles blur the line between writing and visual art. Rabindrasangeet, the form of music and songs invented by Tagore, is an eclectic mix of classical, folk and foreign influences, set to exquisite lyrics that have come to be regarded as a cornerstone of Bengali culture and consciousness.

Rabindranath has the unique distinction of having composed the songs that would later become the national anthems of India and Bangladesh and is said to have inspired the anthem of Sri Lanka as well. His works have been translated into many languages. At the peak of his fame, he was feted by the Western world as the author of Gitanjali, Sadhana and The Religion of Man. His song, Ekla cholo re (‘Walk alone’) inspired Gandhi, and the poems of Gitanjali stirred the imagination of W.B. Yeats and William Rothenstein. Though widely regarded as a poet-philosopher, he was also a brilliant writer of short stories, and had a profound impact on the emergence of the modern Indian novel. In Chokher Bali he highlights the plight of widows, and in Gora, denounces forms of social discrimination based on caste, creed and nationality. His letters are a treasure-trove of ideas, experiences and emotions, and plays such as Raktakarabi remain landmarks in symbolic drama. He also translated some of his own works into English.

Yet Tagore’s reputation, always fragile, stands today at a precarious crossroads between the blind adulation of his diehard admirers and the near-oblivion to which the rest of the world seems to have consigned him. To his devotees at home, Tagore remains ‘Gurudev’, a revered figure beyond criticism. To readers abroad, he still retains something of his earlier image, as a sage from the East with a message that might save the decadent West from disintegration. Tagore, sensitive about his public image, had himself fostered these stereotypes, to some extent. But now it is time to seek out the man behind the mask.

Who, then, is the ‘real’ Tagore? The poet and mystic with his eye trained on infinity, or the stringent social critic whose sharp, unsparing gaze targets the ground realities of his time? The visionary educationist, or the passionate lover of nature? The lyricist who sings of love and loss, rainclouds and thunderstorms, or the spinner of tales who writes so intricately of human relationships in his stories and novels? Is Tagore the presiding deity of Bengali culture, or does he belong to the world?

The ‘real’ Tagore remains notoriously hard to pin down, for his works mean different things to different generations. Certainly, his prescience seems extraordinary. His prime concerns – gender, class, caste, nation, community, language, violence, environment, education, rural reconstruction, literature, art, relationships – continue to haunt us today. His humanism and advocacy of tolerance have not lost their significance for our divided world. ‘We may become powerful by knowledge, but we attain fullness by sympathy’, he insisted. Rabindranath raised his voice against the dominance of some nations over others, but also recognized the power of language, literature, art and music to create bridges of understanding across geopolitical borders.

A pity, then, that young people today know so little about Tagore, for he has so much to offer them. A strong opponent of rote learning, he celebrates the imaginative freedom of the ‘child mind’, its closeness to the miracle of nature and creation. This is the founding principle of Visva-Bharati, conceived as a world university where young students develop their intellect and imagination in harmony with the environment. ‘How intensely did life throb for us! Earth, water, foliage and sky all spoke to us and would not be disregarded’, he says of his own childhood, in My Reminiscences. In a sense, Rabindranath never really grew up, for he never lost his childlike sense of wonder at the beauty of our world.

If the younger generations have lost touch with their ‘child mind’, perhaps it is to Rabindranath Tagore they should turn, to recover something of that magic.

(08.05.2013 – Radha Chakravarty, literary critic and translator, is the co-editor of The Essential Tagore (Harvard and Visva-Bharati, 2011) and the author of Novelist Tagore: Gender and Modernity in Selected Texts (Routledge 2013). She can be contacted at [email protected])

The opinions, beliefs and viewpoints expressed by authors, news service providers on this page do not necessarily reflect the opinions, beliefs and viewpoints of Hill Post. Any views or opinions are not intended to malign any religion, ethnic group, club, organization, company, or individual.

Hill Post makes no representations as to the accuracy or completeness of any information on this site page.