Among its founding fathers, Americans have been particularly critical of Thomas Jefferson in the later part of 20th century. A defendant of slavery who advocated harsh treatment for Native Americans and invited the crisis of nullification, historians like David Malone have been critical of his ideas and actions. In fact what Jefferson has faced is the phenomenon of historical revision, which is not limited within the national borders.

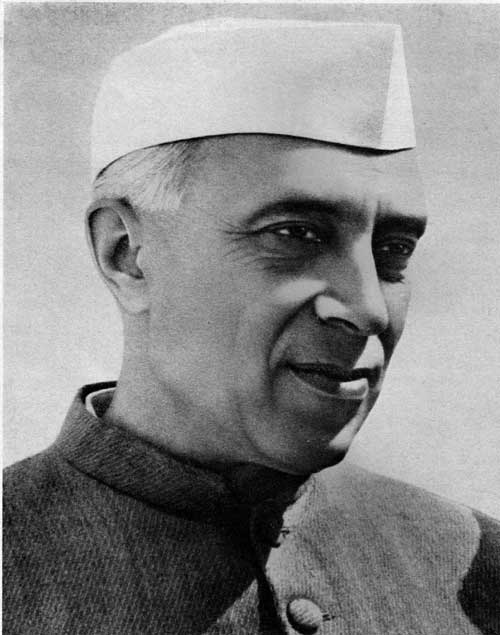

Though much younger than US, modern India has already witnessed its first historical revision. First Prime Minister of independent India, Pt. Jawahar Lal Nehru, became the biggest casualty of it. For a man who starting from the early 1940s acquired a cult following with his charm, intellect, and compassion, a man who for the full part of his Prime Minster-ship remained the idol of the millions, this is a sudden fall from grace.

A recently conducted online survey to find the greatest Indian since Mahatma by a leading English news channel found Nehru lagging at the last position among 10 shortlisted candidates, behind Sachin Tendulkar. Ironically, the expert jury members, part of the same campaign ranked Nehru ahead of everyone else.

We in this article will try to explore different points of criticism of Pt. Nehru and fairness of these criticisms. However it is equally important to note that our first historical revision has also increased stature of some of the other makers of modern India; the biggest beneficiary being B R Ambedkar followed by Sardar Patel.

Many of us today look upon the partition as much the failure of Nehru as it was of Mahatma.

For decades debate revolved around their perceived failure to out-maneuver Jinnah in the 1940s. In 2009 senior Politician Jaswant Singh stirred the pot by writing critically of Nehru for his contribution in the partition. According to him Nehru should be blamed for partition more than Jinnah, as Nehru was adamant on a more centralized form of government. Jinnah had in fact agreed to have a loose federation where provincial governments (possibly divided on religious grounds) will have a huge autonomy. The two were bitterly divided over Cabinet mission’s plan to entrust centre with defense, foreign policy and communication powers, leaving provinces with the residual powers.

Nehru’s insistence on strong central government is an obvious fact, has that lead to partition? The question is dicey at best, because it was not he who gave or considered the option of dividing India. His objection to Jinnah and Cabinet mission has to be seen in the light of his vision of modern India and also before breaking the pot of partition over his head his insistence and negotiations with Jinnah on this issue has to be also considered.

In post independence India, this very vision of Nehru has ensured the relative stability of India compared to our neighbor. It will be apt to first laud him for the stability of union (India) if we would like to blame him for the division of India.

Pursuit of an Imaginary Paradise

In case of Kashmir issue, Nehru’s criticism sounds more credible and rational. The first and biggest mistake was to keep Kashmir matter in his hands rather than giving it to Home Minister Patel, who was doing very well at that time. Another was his inclination towards temperamental Sheikh Abdullah. He also took the Kashmir case to UN, drawing criticism that he should have repelled Pakistan and the tribesmen out of Kashmir first.

He in process, signed a dubious ‘instrument of accession’, promised the plebiscite, and incorporated article 370, which till now remains the bone of contention.

In case of Kashmir, Nehru was more optimistic than practical, and failed to understand the complexity of issues. His failure to decisively close the Kashmir issue in the 1948 has left us all hanging in pandemonium.

The Socialist dream

There is a strong held belief that Nehru’s love for Socialism has been responsible for India’s slow growth till 1990s.

Nehru was educated in London during 1907-1910, at this time socialist ideas of Marx were gaining huge popular support and scholastic interest in Europe. Nehru after the independence insisted upon the public sector ownership and economic growth driven by public sector. In the form of Planning Commission, which was exact replica of Soviet planning commission, he created a centralized driver of economic activities. India grew miserably slow during this phase and the bull run of post reform economy made comparison even starker.

The slow growth of this period has to be also seen in the light of the fact that, priorities at that time were quite different from what they are today. The priority, as it is today was not of ‘shinning India’; it in fact was of a ‘satiated India’. One way of looking at it is as the phase during which India prepared itself for the ‘take off’ of post 1990’s

Also Nehru gave India the socialist form of economy, not the political system, which separates him from someone like Mao who was an adherent of Marxism. If we truly want to appraise Nehru on this front he must be regarded more as the pragmatist rather than socialist.

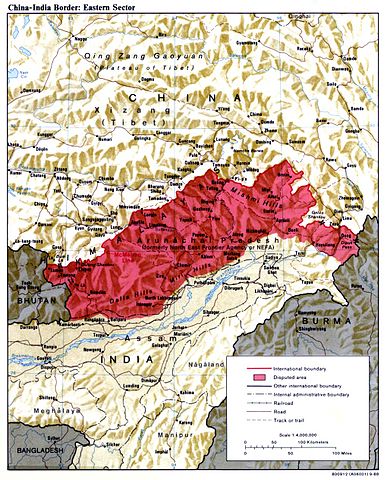

The Chinese Connection

In 1962, China derecognized the McMohan line, dividing India and China and PLA entered into the Indian sovereign land. In the following months it went berserk through all across the border from Ladakh to Arunachal. Nehru was blamed for his ‘Panchsheel’ and overtly gregarious gestures towards China. But the cardinal mistake was not the extension of friendly arm towards China; it was in fact the lack or so to say, absence of any military preparation on India’s part. For instance, Ordnance Factory in Mathura was using its capacity to provide items for public use.

If we are blaming Nehru for unpreparedness on defense front the criticism is justified, but his attempts to build a friendly relationship with China was a diplomatic move which might have been fruitful if the 1962 skirmishes wouldn’t have happened.

This author believes another important thing was that the PRC’s founding fathers were warring Generals, all the politburo members had on field experience of battle during WW2 and Chinese civil war, on the contrary none of the founding fathers of modern India (including Nehru) had ever seen a battle first hand, leave fighting aside.

In the end his failure to see the true Chinese intentions are counted among biggest of his mistakes and unlike all the previously discussed mistakes this one hurt Nehru personally.

He died a sad man, much more diminished in his own eyes.

Conclusion

To an extent this revision is a balancing process of assessing his contributions and qualities to bring him down from the inflated stature that he enjoyed till 1970s. But at the same time we have to see Nehru just like all of us, with all our human fallibilities.

And it is fitting to say that his greatest legacy is ‘education’ in India, much of which has ironically led us to explore ‘the truth of Nehru’.

A note of caution is that unlike Nehru we have the convenience of having wisdom of hindsight, we can see things as they happened and can comment on what should have been done to avert them. The author believes “it won’t be gross injustice just to Pt. Nehru but to the historical facts, to say that in post independence India someone else’s contribution can tower over his”

“…a moment comes, which comes but rarely in history when we step out from the old to the new….” Pt. Nehru

“A moment also comes when a nation looks at its past with a less forgiving view towards its makers.”

Writer is an NIT Hamirpur & IIM Lucknow Alumnus.