Most worryingly, the education being delivered to those in schools is well below global par, while the percentage of school dropouts is conversely above global par. The government, civil society and the private sector thus need to work together to educate Indian youth.

Nearly 540 million Indians are under the age of 25 years. The labour force is expected to grow by 32 percent over the next 20 years, whereas it will decline by four percent in industrialised countries and by nearly five percent in China. India’s favourable demographic profile can add significantly to its economic-growth potential for the next three decades, provided that its young people are educated and trained properly.

India also has one of the largest higher-education systems in the world and ranks second in terms of student enrolment. But while the country has 621 universities and 33,500 colleges, only a few are world-class institutions. The gross enrolment ratio (GER) of 18.8 per cent in 2011 is also less than the world average of 26 per cent. The need for education reform, therefore, has never been clearer.

Global experiences indicate a positive correlation between GER and economic growth in a country and point to the need for a minimum of 30 percent to sustain economic growth. Still, India’s spends only 1.2 percent of its gross domestic product (GDP) on higher education, compared to 3.1 percent in the US or 2.4 percent in South Korea.

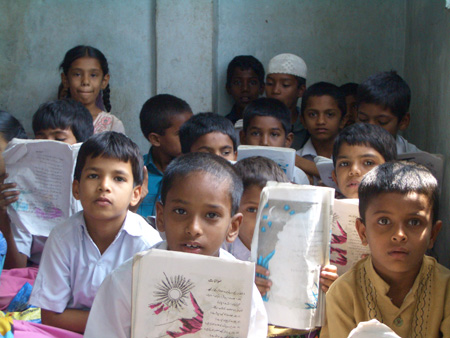

India’s ambitions for the 21st century seem unlikely to be fulfilled without the country taking real steps to fix the education system in very short term. No doubt there are clear improvements in the education system – in particular at the elementary level, where the government’s Sarva Shiksha Abhiyan initiative has seen huge increases in primary enrolment, along with the various mid-day meal schemes, which attract poorer sections of the population.

But this or even overall increases in literacy are far from sufficient to prepare young people for productive employment. A fast-growing economy needs young people to be educated in such a way that they can make responsible life choices, get the right jobs and lead communities towards positive change. The fundamental and troubling question is: How will India’s millions be educated?

The government closely guards the Indian education sector while the judiciary has given it a very loosely defined not-for-profit tag. Accordingly, investments need to be carefully structured so that they cannot be construed as profiteering from students.

While there is a clear recognition that private and non-governmental funding of education is needed, there is lack of clarity on the form that acceptable financial returns from this sector might take.

The current legal and regulatory framework does provide opportunities for joint ventures between foreign educational institutes and Indian institutions in the K12 (kindergarten-12th grade) segment, higher education institutions (HEI) and non-formal institutions (NFI). Among them, the NFI segment is particularly suited for foreign investment and strategic alliances. It operates outside the regulatory constraints on foreign investment in many cases.

Although 100 percent foreign direct investment through automatic route is permitted in the education sector, the present legal structure in India does not allow the grant of degrees by foreign educational institutions, thereby restricting independent operations by foreign players.

The government has therefore introduced several important bills in parliament relating to accreditation, foreign universities, educational tribunals and unfair practices to completely restructure the legal and regulatory environment of higher education. There is also a growing recognition within the Indian government that the demand-supply gap in the education sector has to be bridged through opening up participation from private, non-governmental and international players. But political opposition has stalled the legislative progress of some of these measures.

While regulatory changes are long overdue, there is a lot that can be done within the existing structure and regulation of education in the country. Besides, the main gap is that of translating plans into action and making projects operational.

Early stage tax and regulatory advice is a must so that such pitfalls can be worked through in an investor-friendly manner. The real issue is one of quality and this permeates every layer of education from primary to higher.

India can benefit from building stronger bridges to global centres of educational excellence. There is also a real global interest in making a success of Indian education. The country must be one of the leaders of the 21st century’s knowledge economy.

Big businesses need to realise that government control over education is receding. They must search for their place in a sector that has the potential to attract $100 billion in investment over the next five years. Businesses also will have to keep in mind the market incentive to invest in education towards change. In a multi-stakeholder approach, businesses can partner with non-profit organisations for creative ideas, and with governments for scale and experience.

The challenges are no doubt enormous. There are children from families too poor to think about education, beyond the reach of schooling and too malnourished to study. There are too few schools, classrooms, teaching resources and adequately trained teachers. Rampant illiteracy underpins other problems including exploding populations, gender imbalances and poverty. But it is for the government is to ensure that appropriate policies are framed and meticulously implemented to meet the future aspirations of India’s youth.

The authors are partners at The Hearth Education Advisors, a specialised advisory firm focussed on improving the delivery of education. The views expressed are personal. Shashank Vira can be reached at [email protected] and Mark Runacres at [email protected]

The opinions, beliefs and viewpoints expressed by authors, news service providers on this page do not necessarily reflect the opinions, beliefs and viewpoints of Hill Post. Any views or opinions are not intended to malign any religion, ethnic group, club, organization, company, or individual.

Hill Post makes no representations as to the accuracy or completeness of any information on this site page.