Leaving Istanbul we headed South on to the Anatolian Plateau to the exotic Cappadocia region. Goreme then Konya, home to the famed Whirling Dervishes. There would be no Konya or the Whirling Dervishes if it were not for Jalaluddin Rumi.

Rumi was born in Balkh, in the Khorasam district of Persia. After a pilgrimage to Bagdad, Mecca, and Damascus, the family eventually settled down near Konya in a village called Rum. Hence Rumi.

Rumi today is closely identified with Sufism and Sufi Mysticism within Islam where devotees sought a mystical union with God.

During his travels, Rumi met Shams ad-Din meaning The Sun of Religion, a wandering Sufi from Tabriz.

The two, with their combined ideas and thoughts, became the bed-rock of Sufism. Shams ad-Din became Shams Tabrizi. One day Tabrizi disappeared. Rumi’s outpouring of grief led him to write poetry called ‘Ghazal’. Rumi would dictate while reciting his poetry and would pace the room in circles. This was the birth of the Whirling Dervishes. Dervish means doorway and is believed to be the mystical portal between the earthly and the cosmic world.

Rumi’s grave in Konya is known as the Green Dome.

From Konya, we headed north to Erzurum to catch the highway to the Iran border. The frontier post was in the shadow of Mt. Ararat. This is where Noah’s Ark was supposed to have landed. The last 200 kilometers of road in Turkey till the border was an absolute abomination!

Our first night in Iran was spent in Tabriz, Shams ad-Din’s home town. From there it was an easy drive to Tehran. The roads were the best since leaving Europe. Wide, smooth, blacktopped, and little traffic. Surprise! The traffic police patrolled on Harley- Davidson’s that belonged to a by-gone era. The front shockers had coil springs!

We were stopped umpteen times by the police with ululating sirens. Because of the sparse traffic, this was their only entertainment. The Canadian license plates on Bucephalus were a rare sight.

Tehran was like a cold bucket of water poured on the head. The traffic was impossible. Somehow the car is a common denominator in this Asiatic habit of aggression. The road is a battleground.

David and I drove with the utmost care to prevent any damage to Bucephalus. Delhi was still 5,000 kilometers away.

There was no real reason to stay in Tehran so after a couple of days we headed for Persepolis. Persepolis was of special interest to me. The razing of Persepolis by Alexander was a move contrary to anything that he had done on his entire campaign to India. I had done all my historical homework but I did want to see the ravaged city that had survived in bits and pieces in the Iranian deserts. I took photographs by sunset and by sunrise the next morning.

Darius the Great had built Persepolis around 515 B.C. It was known as the ‘Takht-e-Jamshaid’ and reputed to be the most spectacular city in the world, the Jewel of Persia and Capital of the Achaemenid Empire.

In 480 B.C. the Persians had destroyed Athens by fire and sword. Alexander wanted revenge. Revenge for the desecration of the Acropolis in Athens by the Persians during their invasion of Greece. Alexander had always shown mercy to the people he conquered, actually rehabilitated them, not so this time. After having taken over the city, Alexander held a banquet to celebrate. Alexander loved his drink and late in the night in a drunken stupor, he gave the order to loot, pillage, burn and raze the city to the ground!

The Macedonians did just that!

Next on our itinerary was Esfahan. It has to be one of the most beautiful towns in the world. Magnificent monuments built out of blue ceramic tiles. It was Persian artisanship at its zenith.

And on to Mashhad.

From Mashhad, we crossed over into Afghanistan at Islam Qala and spent our first night in Herat. Herat was the Easternmost city to be named Alexandria. The Mud Fort, which is referred to as Alexander’s Citadel was his winter headquarters, still stands. He waited for his scouts to bring him information as he planned his spring invasion of India.

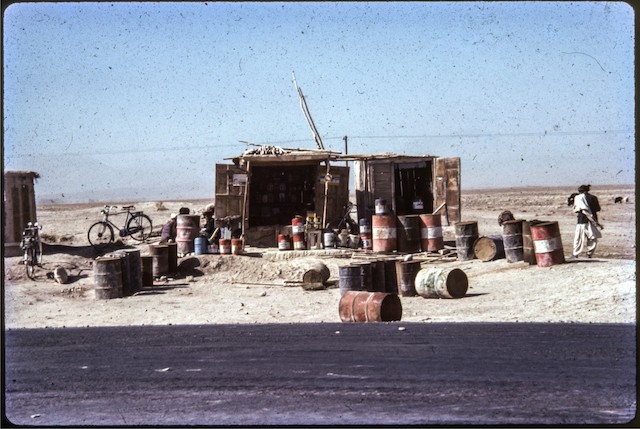

From Herat, Alexander took the direct route to Kabul across the desert. We took the road via Qandahar.

The drive from Herat to Kabul was the longest single-day drive, 650 kilometers. Bucephalus simply flew over those roads without a hiccup. Smooth, cemented roads built by the Russians in the 50s. The specifications were that the road should be able to take two-tank transporters side by side. Also straight as an arrow for five kilometers to land a MIG aircraft. The Russians were looking for a warm water port, as they had been for centuries. That never happened but these roads were most helpful when a thousand Russian tanks rolled into Afghanistan overnight in 1979.

On the drive to Kabul, we passed Qandahar which has the largest Mud Fort in Asia.

We also passed Ghazni and Ghauri. The history of India is incomplete without reference to these names.

Having touched all these historic places the excitement of being in Kabul and then crossing the fabled Khyber Pass was building up.

The Khyber Pass held center stage to a lot of the stories I heard in childhood. The geopolitical situation of the Khyber Pass is responsible for shaping India’s history. Little wonder the Khyber mystique gave me goosebumps!

Other than the history we were absorbing along the way, we ran into a sand-storm. What we experienced was highly unusual. I was driving. The wind started to blow and sand would sweep across the road. I slowed down. The wind speed increased. The sand would come in sheets and visibility was reduced to about 15 meters. The wind started to howl, shriek, and rose to an ear-splitting crescendo. The sand, blowing and swirling creates a low-pressure area a couple of 100 meters above the surface. This creates a vacuum. Nature hates a vacuum so everything moves into that vacuum area. In this case only sand was available. Bucephalus with David and me was too heavy to lift!

We sat there, shell shocked! Nothing moved, in total silence, nearly pitch black, ears popping. We were in a vacuum!

Frightened as I was I did have the presence of mind to keep the windows rolled up. That saved us!

I put on the dome light and jotted down notes, just in case I did not survive this ‘happening’! My family and friends would know what happened to me in my final moments on terra-firma! That evening in the hotel dining room we discussed this with the locals. When I mentioned this ‘happening’ there was a dead silence. Everyone in the room came to talk to me and tell me that I was lucky to be alive! It was a freak ‘happening’! They had heard of this phenomenon but had not met anyone who survived.

Had we not been sitting, cocooned in the car with a cabin full of air, this could have been fatal!

Had we been in the open, the low-pressure area created would have sucked the air out of our lungs!

Stories abounded of nomads along with their camels who were found dead. Suffocated! We lived to tell the tale!

It was a great evening at the Plaza Hotel in Kabul. Drinks were on the house as was the dinner and the hotel room. The Afghans are most magnanimous with their hospitality and appreciate heroes! That night David and I were heroes!

About 2,000 years before the Gateway of India was built in Bombay by the British there existed another Gateway to India on the Northern boundary, the Khyber Pass, one of the most famous and important passes in the world.

Starting with the Aryan invasion of Alexander, all came down to the Khyber. As did Muhammad Ghauri, Mahmud of Ghaznavi, Genghis Khan, Tamerlane, Nadir Shah, and Babur, to name a few. It is important to note that they all came down to the Khyber. No one succeeded in going up the Khyber. The terrain was too difficult, dangerous, and demanding. As such the mountain range of Safed Koh came to be called Hindu Kush, the killer of Hindus!

In any case, the Hindus were a peaceful, vegetarian people, known for their philosophical thought and not inclined to adventurous conquests. That was left to the British and the Sikhs.

To quote Mathew Arnold on Alexander’s invasion of India, “She (India) let the legions thunder past and plunged into the thought again!”.

So the hordes continued to thunder down the Khyber and plunder India.

The Khyber Pakhtunkhwa, as it came to be known, was lorded over by Mahmud of Ghazni. Rather than make the arduous journey up and down the Khyber he controlled the area from Lahore where he had shifted his Capital from 1151 – 1186.

The various tribes like the Pashtuns, Afridis, Yusufzai continued to control the area. It was not possible to govern them.

In 1526 Babur defeated Ibrahim Lodhi and took Peshawar. The region, Pakhtunkhwa, was never subjugated. Various Kings and conquerors came and went. Sher Shah Suri, Nadir Shah, Ahmad Shah Durrani. It was an impossible task to control and govern the tribes.

The Kingdom of the Sikhs was established under Maharaja Ranjit Singh. In 1818 he invaded Peshawar and captured it from the Durranis. The exit from the Pass into India was sealed. Ranjit Singh’s General Hari Singh Nalwa was the man responsible for this. His name is still mentioned with awe!

Sikhs from Punjab came and settled in the Khyber Pakhtunkhwa region. They built the Bala Hissar Fort and the only Gurudwara in Peshawar.

The Anglo-Afghan Wars were fought as were the Anglo- Sikh Wars. Nothing changed. The Durand line was drawn demarcating the border between Afghanistan and British India. The tribes did not respect this border. They don’t till this day.

During the 1857 uprising, the tribes stayed neutral and some even supported the British. They all had one thing in common. They despised the Sikhs whose presence and power continued to grow.

The reason for the free-living, tribal thinking peoples of the area is their strict tribal code of conduct called ‘Pakhtunkwali’, Honour, Hospitality, and Revenge and Right to Refuge.

We left Kabul and spent the night in Jalalabad, the last town in Afghanistan. We wanted to get an early start and then take a leisurely drive through the Khyber Pass and to get to Peshawar before sundown.

It was a cold wintery morning in Torkham, the border town in Pakistan. We sat on charpoys sipping hot tea while the Pakistani officials checked passports and Bucephlus. Everyone was surprised at seeing a real live Sardar! They had never seen one before, only heard of them!

They were happy to buy us umpteen cups of tea and packets of biscuits. We got our clearances and we were on our way. The last-minute advice from one of the officials was, “Sardar jee, you are entering a totally lawless area (gair ilaka!). Do not stop, do not take photographs, do not talk to anyone, or give them a lift. It is 5 kilometers to Landi Kotal which is the top of the Pass. Once you come down the other side, you will be safe!”

Finally, I was going to be crossing The Khyber. Rudyard Kipling described it as “a sword cut through the mountains”. The summit is only 1,070 meters above sea level but the sides are near vertical.

The overland drive from London had been a success. David was driving, I had my Nikon ready. The words of George Molesworth a British Army officer came to mind, “Every stone in the Khyber has been soaked in blood!”

George Molesworth had good reason to say that. Britain fought three wars against the Afghans but never with a successful conclusion.

In the first Anglo-Afghan War, 1840, a force of 16,000 British troops, consisting of 4,500 professional soldiers attempted to quell the indigenous people with force with disastrous consequences.

The entire force was wiped out, only one man survived, and that too for a good reason. He was to be a messenger. The message was, “Go tell your masters what happened to your army!”

As we reached the summit, a portion of the mountain had been cleared and memorials to the British Armed Forces who had served in this area had their crests inscribed on the stone wall. They were in remarkably good condition, they were being looked after. The shrubs had been trimmed, no weeds. The largest one caught my attention.

“David stop!”, I yelled. He did. Throwing caution to the winds and ignoring all the good advice I had been given, I started photographing the memorials. One of them was dedicated to 54 Sikhs Frontier Force, Chitral 1922-23.

I was so absorbed in photographing that I did not notice the two tribals who appeared out of nowhere and moved as silently as ghosts.

They were rugged looking in homespun clothes, big turbans, sunken eyes, hawk-nosed. A very Semitic look! The man who had come up to me had a jezail rifle slung over his shoulder. He stood quietly giving me a ferocious look. These tribals are extremely good looking people. His look had a certain amount of awe, surprise, and tons of authority. The surprise was definitely that he had not seen a Sadar at the top of the Khyber or seen a Sardar at all! But he had heard of them in his childhood stories.

I looked over his shoulder, the second man, similarly attired, jezail held in both hands was peering intently at David. If a Sardar was a strange sight, this Yorkshire man with fair skin, freckled face, and red hair and beard was an apparition! Both men were so surprised that they did not really know how to react. It did occur to me that David and I would be suitable trophies at the tribal bonfire that night!

With a very dry throat, a thumping heart, and Nikon still pointed at my man I decided to break the ice.

Placing my right hand over my heart, and bowing my head, I cleared my throat and said, “Salam Al Ekum Agha!”

I had learned in Iran that ‘Agha’ is an honorific title for a very senior person.

He kept staring at me and tried to smile, something he was not used to. That little flicker of his lips sent a message to me.

The silence was broken when he said, “Sardar!

Quietly, I breathed a sigh of relief! I would live to see another sunrise!

Now that I had broken the ice, Nikon in my left hand, I put out my right hand and said, “Dost”!

Without hesitation, he gripped my hand in a vice like grip. No words.

I pointed out to the memorials and said, “Bahut Khoob!”.

I knew he understood me because these nomads speak Pashto, Urdu, Farsi, and I would not be surprised if they spoke a smidgen of English and Russian.

“Bahut Khoob, Agha, Shukraan”, I said.

“Sardar, hum dushman ki kadar karta hai!”, he said.

It was the compliment of all compliments!

Since we had become friends, I did not hesitate to take a number of photographs of the man.

We reached Peshawar and checked into Flashman’s Hotel for a well-earned drink.

While in Tehran I had made contact with an advertising agency. They contacted me in the winter and wanted me to do some photographic work for them the following year. This involved driving to Tehran and back. I had no co- driver so I did the drive solo. And to my utter delight I was to cross the Khyber Pass twice again. Once on the way to Tehran and then again on my way back to Chandigarh.

H.Kishie Singh is based in Chandigarh and has been a motoring correspondent for newspapers like The Statesman, New Delhi, and The Tribune. His column ‘Good Motoring’, for The Tribune ran for over 27 years. He has been also been the contributing editor for magazines like Car & Bike, Auto Motor & Sport, and Auto India. His latest book Good Motoring was published recently and has co-authored a book with The Dalai Lama, Ruskin Bond, Khuswant Singh, and others, called The Whispering Deodars.