Knowing our taste for ghazals, I completely believed him. But the problem was I, being just a student, did not have a reel-to-reel tape recorder. But soon I found one and we were enthralled to find out that it was a recording of an upcoming Pakistani ghazal singer Mehdi Hassan who was singing his famous ghazal, “Gulon mein rang bhare”. We loved it. So far the only ghazals I had heard were all sung by Begum Akhtar such as “Aye muhabbat tere anjam pe rona aya”.

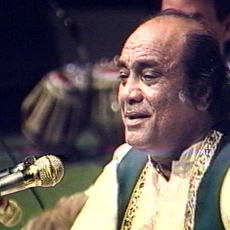

It so happened, the next time I heard Mehdi Hassan was after I had arrived in Washington as a student in the 1970s. I think, it was his first live concert in Washington and I was excited that I am going to see him sing live on stage, almost “roobaroo” (face to face).

And for more than two hours he showed us how a ghazal should be sung, how it can be composed in an Indian raga to make it immortal, and how and when, which part of the verse should be highlighted. Basically, what I felt was that only Mehdi Hassan could bring the real meaning and spirit of the ghazals and tell you with great ease what the “shayar” (the poet) really wants to say. It could be “Yeh dhuan kahan se uthta hai” or “Yeh rakh akhir dil na banjaye” or “Ranjish hi sahi”.

And much later after another concert in the US capital, when I interviewed him on behalf of Voice of America, he confirmed all of what I had thought about him and his magic. He said he chose to compose them into ragas because a raga, be it Bhairavi or Darbari, always sounds fresh and once a ghazal is composed in that raga, the ghazal will always remain popular and never die. And he said he always tries to find out what is the “bhava” or the “emotional premise” of a particular ghazal and then chooses a raga that can bring the poet’s feelings out so that they can touch the hearts of the audience.

And today, most music lovers will agree with me, that all his ghazals were composed in a way that even today they magically highlight the poet’s feelings in a way that they really overwhelm us.

That is why, unlike others, I don’t call him the King of Ghazals as people have often described late Jagjit Singhji, another stalwart. I love Jagjit’s gayaki also, but for me he with his heavy voice and subtle nuances, was like a “very well-trained horse who was running on a well defined track” while Mehdi Hassan for me is like a “wild deer running freely, hither and thither, in green pastures or sometimes in dense jungles, but always coming back to the basic raga and or as they say in Hindi, the ‘sum’.” I find Mehdi Hassan even two notches above Ghulam Ali sahib whom I also admire very fondly.

So instead of King of Ghazals, I like to call Mehdi Hassan a “ghazal traash”, who, by his “gayaki” and purely magical voice, chisels an imaginary and abstract statute of sounds – the ghazal. The notes are so true that it is difficult sometimes to separate his lower notes from those of the harmonium.

I always feel he is like a “sangtraash” who first chooses, say a sad romantic ghazal by Ahmed Faraz, and then selects a raga to go with its mood, and then with his skillful husky voice and true notes, he gives the ghazal its real shape – sculpting at some places and chiselling at others – to bring to us the real “emotional premise” of the poet, the true spirit in which it was written. And he is always successful in doing so and warming our hearts, because he does that with the most appropriate Indian raga.

For me, he brought and established a new era in the ghazal gayaki. The styles of the ghazal gayaki will be always known as “the pre-Mehdi Hassan era”, and “the post Mehdi Hassan era” styles. And no wonder in this “post Mehdi Hassan era”, we see so many male Ghazal singers trying to follow his style.

I can never forget how my little son and daughter, sitting in my lap in my family room in Virginia, used to listen to Mehdi Hassan, even though they did not understand the language. But the result is heartwarming. My son Brittan is always questioning me about the different ragas and their moods and wants me to leave for him my huge collection of Mehdi Hassan ghazals once I depart this world. And my daughter Samiha loves Indian classical music, and the other day, called from Durham to ask me what the word “suroor” means in Urdu.

My last “roobaroo mulakat” (face to face meeting) with the maestro was in Washington on a beautiful summer evening at a live concert arranged by the Smithsonian Institute in the lawns of one of their museums. I can never forget when my ghazal god, limped as he rose from the chair, and with great difficulty and with the help of his sons, slowly climbed the 10 or so stairs to reach the podium. I was sitting on the lawns below among some 150 fans, with my friend Shekhar and his wife Urmil (the most ardent fans of Mehdi Hassan I have found till today). We were concerned why the maestro is physically faltering and wondered whether he will be able to sing as usual. But when he began singing in his “even deeper and huskier than before” voice, we were reassured that the “shola” (fire) is still not extinct at all.

And now that he is gone, and his voice fills the stillness of my small living room in New Delhi, I wonder if ever there will be another Mehdi Hassan, my “Ghazal traash”. And as his voice takes over the silence of the room around me, singing “Shola tha jal bujha hoon, hawaein mujhe na do, mein kab ka ja chuka hoon, sadayeien mujhe na do”, I feel tears quietly rolling down my cheeks. And I feel he will live forever. He can never die – not for me or for anyone who loves ghazals, and definitely not for anyone who is a serious ghazal singer.

(Ravi M. Khanna is a longtime South Asia observer and a lover of classical music. He just published a book called “TV News Writing Made Easy for Newcomers”. He can be reached at his website newsexpertravikhanna.com)

The opinions, beliefs and viewpoints expressed by authors, news service providers on this page do not necessarily reflect the opinions, beliefs and viewpoints of Hill Post. Any views or opinions are not intended to malign any religion, ethnic group, club, organization, company, or individual.

Hill Post makes no representations as to the accuracy or completeness of any information on this site page.