Manali: Rahul Bhushan, the man who saw tomorrow is working to give the 1000-year-old Kath Kuni architecture a new charter of life. His work is a tribute to the rich artistic heritage of the state and an evidence to the power of tradition in shaping conversations around sustainability .A few years ago, on an spontaneous break, he had made his way to the picturesque Kullu Valley, marked by stunning emerald forests set against the snow-capped mountains, straight out of a postcard.

The Naggar Castle, once the seat of the region’s powerful Kullu kings, stood out in this glowing imagery, which had endured the ravages of time and calamities to stand tall as a hotel today. But that is not what enthralled him; Naggar Castle is the embodiment of the vernacular architecture of Himachal Pradesh, called Kath Kuni, which has been in this region for a thousand years.

Kath kuni homes have interlocked wooden beams made of deodars that steady the stone-supported structure, even in the face of earthquakes, providing insulation through the double-layered walls. The houses, much like the knowledge they hold, were passed down from one generation to the next. Yet, despite their awe-inspiring structure, this native architecture is slowly being erased from modern memory as urbanization digs its root deeper. Most families in Himachal have left their ancestral kath kuni homes and moved into concrete houses . But the skills and heritage associated with Kath Kuni continue to charm and enlighten, and it is this tangible heritage that architect Rahul Bhushan is trying to preserve.

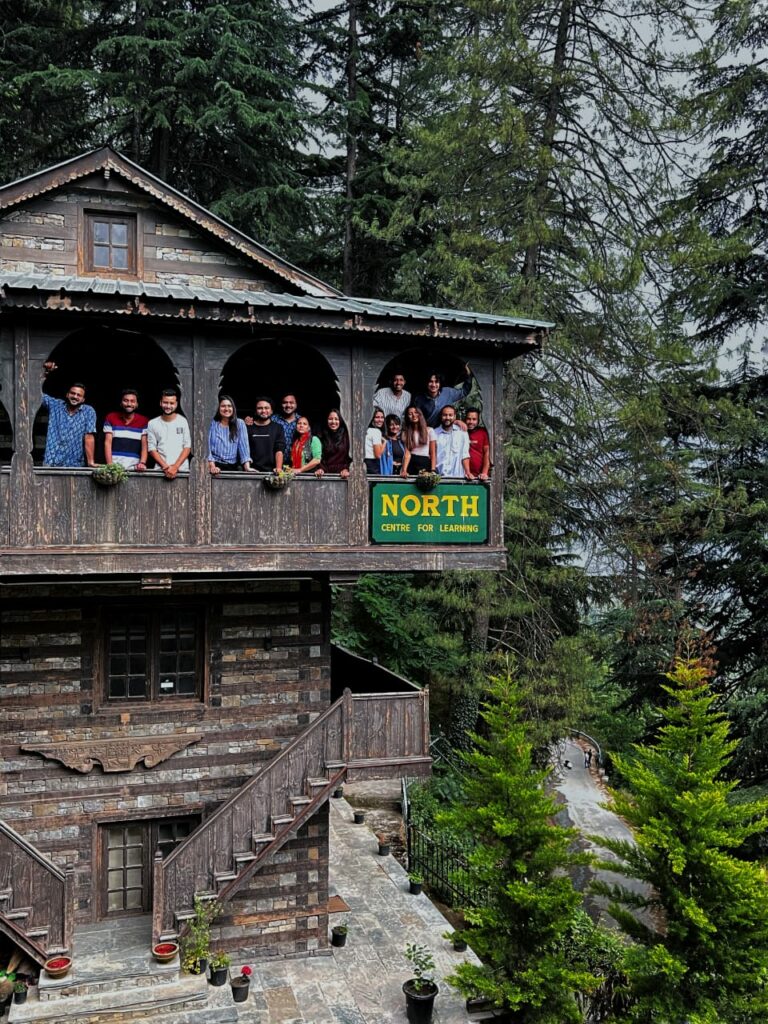

During his masters, Bhushan, originally from Himachal’s Shimla, spent two years researching ancient Kath Kuni architecture. But the seeds for change had been sown earlier. Rahul revealed “During my bachelor’s, I got instantly aligned with design thinking and problem-solving, an approach to life that I could take forward, and that’s when I started a club in college. It was for people from all creative backgrounds to come together and create magic,” It was the foundation that created North, a Naggar-based design and architecture studio dedicated to preserving traditional architectural techniques. A team of karigars working on building a kath kuni structure.

But what about Kath Kuni, which translates to ‘wooden corner’, merited this attention? Bhushan believes the building method to be ingenious and practical. He added “It is not just any technique but an art of building natural homes, without nails and bolts using wooden joinery systems. Kath kuni houses are built like Lego structures that can be dismantled rather than demolished, which opens a scope to reuse the material from old abandoned houses in the region. To build a kath kuni house, the whole village comes together and lays the wood and stone in union, passing the legacy of the skill from generation to generation”.

But in Himachal, where kath kuni homes were once a source of shelter, they are slowly disappearing. Among many reasons is the expensive raw materials, i.e. timber, lack of kath kuni practitioners and easy access to alternative materials. Plus, dependence on wood does not make the architectural style a sustainable choice. But Bhushan aims to change that perception.

Rahul said that “Compared to cement construction, one of the world’s worst polluters and extremely unsustainable, India’s vernacular architecture has a minimal carbon footprint. Raw materials, such as wood, and stones, are all accessible naturally and can be reused because they have a long life; think of kath khuni houses, which have stood strong for centuries. All the material from old houses can be reused to construct new buildings, while concrete buildings often have an average life of 50 years,”

One way to access timber is sustainable forestry, where forests are planted for raw materials, creating a sustainable cycle, and is within the scope of North’s research areas. Additionally, they innovate on sustainable architecture, make eco homes, practice perm culture and share this knowledge through workshops.

Undeniably, there is a great need to preserve and promote India’s vernacular heritage. Himachal falls in some of the Himalayas’ most seismically active zones, making it prone to earthquakes, flash floods and other natural calamities. Hence, the region’s architecture must be resilient to these challenges. Kath Kuni is the best example of region-specific architecture. To promote this knowledge.

“We host lectures and practice research on applied sustainability, Himalayan architecture, creative design thinking, natural building and revitalization of indigenous building systems such as Kath Kuni and craftsmanship of Himachal Pradesh,” Rahul explains, “To share the knowledge we have gained, we take vernacular creative thinking workshops for students of different design colleges throughout India along with hands-on learning of the crafts of this region through our workers . We do everything from wood carving workshops, metal beating, and natural building to vaastu.”

Members at his aragaintion also assist clients in building new structures by reclaiming stone and wood from abandoned kath kuni houses. They are designing a true authentic log house for a client who wants to make their home in Himachal, an artist’s retreat home in Naggar, restoration projects, tiny cabins and a few projects for local villagers. In the day and age where modern architecture has permeated the deepest nooks and corners of the world, Rahul hopes that walking the talk will inspire the younger generation to safeguard the indigenous craftsmanship of the place they call home.

Sanjay Dutta, an engineer by qualification but is a journalist by choice.

He has worked for the premier new agency Press Trust of India and leading English daily Indian Express.

With more than a decade of experience, he has been highlighting issues related to environment, tourism and other aspects affecting mountain ecology.

Sanjay Dutta lives in a village close to Manali in Kullu valley of Himachal.

Good that Rahul Bhushan has taken this intiative and you have written about it, thanks.