Introduction

Early in the last century, when most transportation was mainly through horse-driven carriages, a saees (ostler) was required to groom the horses. Although various types of horse-driven buggies can still be seen in many parts of India, as also bullock carts, the advent of the automobiles made this transportation mode obsolete, thereby eliminating the need for a saees. This transformation resulted from changes in technology and not by Government intervention. In a similar manner, the apple mandis in vogue – which evolved from the centuries-old, inefficient wholesale sabzi mandis for vegetables – will be replaced by more modern, direct grower-to-consumer distribution systems, in which the current arthis (commission agents) will have no place. Unfortunately, apple growers are trying to ‘reform’ this doomed, archaic system, and that too through government intervention! Instead, farmers should be exploring the new, rapidly evolving direct farmer-to-consumer markets. Also, they continue to grow the over century-old ‘Royal Delicious’ sport (strain) of Red Delicious that sells for about a third of the price of modern sports such as SuperChief, Gala, and Fuji. This article traces the evolution of apple marketing in India, and attempts to analyze the rapidly evolving changes in apple marketing, and the move towards growing modern apple cultivars (varieties) such as Gala, Fuji, Jonagold, and Honeycrisp.

Evolution of the Current Arthi-Mandi System

Before 1947, a contractor would buy most of the meagre standing crops from Ilaqa Kotgarh and transport them on mules for sale to a commission agent in Shimla. Following Independence, displaced persons from Pakistan resettled in Delhi became commission agents for apples. After 1947, the bulk of the produce from Ilaqa Kotgarh was forwarded by two local shopkeepers to one of two commission agents in Delhi. The payments by these commission agents remitted through the postal service, were passed on to the growers by these shopkeeper-forwarding-agents.

Until 1958, Australian apples were imported by commission agents through ports in Calcutta, Madras, and Bombay. The 1958 import ban on Australian apples forced these commission agents to focus on Indian apple growers. While the commission agents from Bombay focused on Kashmir, the ones from Calcutta and Madras chose to work with Ilaqa Kotgarh.

Early on, when most of the apple production in Himachal Pradesh was in Ilaqa Kotgarh, intense competition amongst these commission agents made them solicit produce from growers. Wooden boxes from several orchards were required to make up a full load for the small trucks in use. For a small commission, several forwarding agents made the arrangements for sending produce to commission agents. In the beginning, apples were directly trucked to metropolitan centres such as Delhi, Calcutta, Bombay, Ahmedabad, Hyderabad, Madras, Bangalore, and Coimbatore; but because of restrictive, state-based truck licensing, the consignments had to be transhipped between trucks several times. Intense competition amongst the commission agents helped the growers with better service.

As the output of apples from the Ilaqa grew, the attention of the commission agents shifted towards larger growers who were able to supply apples in truckloads quantities. The visits to the smaller growers dwindled; they began to be serviced by local commission-based agents appointed by the commission agents.

With the spread of apples across the state, the production became so large that commission agents no longer had to vie for a limited supply. With this change Delhi evolved as a centralized mandi (wholesale market) to which most produce was sent, from where it was redistributed all over India. It became easier for commission agents to directly order truckloads from Delhi, resulting in Delhi becoming Asia’s largest fruit mandi.

Downsides of the Arthi-Mandi System

The centralized mandi system had several down sides: The services provided to the growers declined as fewer commission agents handling very large volumes reduced competition. And small growers found it difficult to receive payments for produce sold; it was not uncommon for growers to have to go to Delhi to recover payments due. The older grower-commission agent bond, which made the growers feel comfortable with prices fetched in the market, began to disappear.

Furthermore, because of congestion in the Azadpur Mandi in Delhi, trucks bringing apples from different parts of Himachal Pradesh and Kashmir sometimes had to wait outside the Mandi for several days; the moisture from the transpiration of packed fruit and the heat in the tarpaulin-covered trucks resulted in rapid fruit degradation. And the very poor manhandling of apple boxes during the loading-reloading process resulted in excessive fruit damage, about which the entire mandi-related transportation system was oblivious: almost as bad as shipping apples in gunny sacks, like potatoes! So, orchardists taking pains to properly pack apples, had little effect on the final very badly damaged apples received at the rehris – perhaps, the main reason for the low prices fetched by orchardists.

The two, relatively recent, misguided practices of ‘overpacking’ further exacerbate damage to apples: First, trays are ‘overpacked’ by increasing the grade of apples packed on a tray meant for a lower grade – “You should not be able to see the tray while looking down on a packed layer is the refrain.” For example, large-size apples are packed on medium-size trays. When compared with standard packing, this practice results in more apples in the box. As an example, while a standard medium-packed box weighs about 22 kg, the large apples in medium-tray packed boxes weigh about 24 kg (Figure 1). In the many road-side mini-mandis the buyers want the boxes to weigh more. This unfortunate trend, which started in Kotkhai, has been emulated by the rest of the state. It results in significant damage to apples due to lateral touching.

Besides the arthis asking for more weight, growers give two reasons given for these two practices: Savings on the cost of boxes and transportation, in which the freight depends on the number of boxes and not on their weights.

Second, additional layers of apples are packed in boxes. Such artificially increased-size boxes do not easily fit in trucks; it is not unusual for the boxes to be packed in trucks by either kicking or jumping on the boxes. These two practices result in enormous damage to apples; as a result, when the apples are finally sold on ‘rehris’ the damaged apples understandably fetch very low prices. Who started these practices – growers or arthis (commission agents) – is equivalent to the question: which came first, the chicken or the egg? Not to be outdone in compounding this misguided practice, apples have been marketed in apple ‘box drums,’ which have almost twice the height of a standard telescopic box, and weigh about 42 kg (Figure 2)!

Blame Game for Low Apple Prices

Understandably, orchardists are frustrated by the low prices for Royal Delicious apples – currently the overall bagicha (orchard) average is, at most, in the Rs 40-45 per kg range. What with input costs – such as for labour, transportation, plant-protection and plant-nutrition, cardboard boxes, and trays – continually increasing, profit margins are decreasing. If this trend continues, growing apples may soon become unprofitable.

of apples in nine layers!

So, the blame game begins – someone must be responsible. “Look at how high the retail prices are.” “Why are orchardists not getting their fair share?” The first target is the arthis – “They control the prices,” “They come only to make a profit, and are not interested in the apple industry.” Next, it is the Controlled-Atmosphere (CA) Stores, such as those of Adani AgriFresh – “They artificially lower the purchase price and control the market.” The CA stores represent less than 2% of the apple market and, as such, it is naive to think that they can control the prices. It is true that the prices do drop about the time the CA stores open and declare the purchase price, which subsequently are adjusted to account for changing market prices. But that does not cause the price drop: Rather, as good businessmen, they wait for the cyclical annual drop in apple prices before beginning their seasonal purchase of apples. And, CA operators do offer higher than current market prices for superior apples.

“Look at the very large differences between wholesale prices, fetched by farmers, and the retail prices. We are being cheated by the arthis and the corporates,” is the refrain. Most farmers are not aware of marketing costs. They happily pay Rs 20 for a small 20g bag of potato chips, which works out to a retail price of Rs 1,000 per kg for the potatoes, nowhere near the wholesale prices that growers get!

The suggested panacea for the low prices is Government ‘action’ – “Government must subsidize fertilizers and spray material,” “Government must enforce the APC rules,” “Government must set up an MRSP for apples,’’ “Government must increase the purchase price for apples,” …

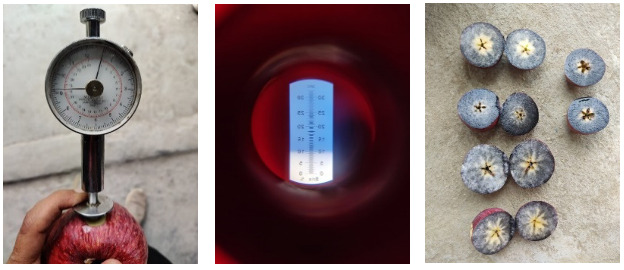

We must understand that the prices of apples are set at the retail level, such as at the rehris, by customers: highly damaged apples fetch lower prices, which reflect all the way through the arthis to the grower (Figure 3). Until growers revert to proper packaging to prevent fruit damage, and work towards better transportation chains – in which apple boxes are not opened, and poorly repacked on the way – the prices fetched by growers cannot increase. It’s up to the growers to embrace such practices; expecting the Government to solve such problems is just wishful thinking.

Overpacking and increased number of apple layers in cartons cause excessive damage to apples. In view of this end result, why pack apples in cardboard cartons, and not ship them in gunny sacks, like potatoes? Other than the care taken in growing apples, the end result of the current practice is equivalent to treating the higher priced apples like potatoes, resulting in much lower prices.

Recent Changes in the Arthi-Mandi System

Some marketing innovations started around the year 2000. By using up-to-date market information, the first of these innovations used the internet to directly sell truckloads of apples at the orchard itself. In this way the growers were able to bypass the major mandis. However, this marketing innovation was short lived: In this experiment, an agent would inspect the produce of a grower – say by examining 20 boxes – and use the internet to make a sale. This model failed because many growers took unfair advantage by not supplying the quality shown and paid for.

Around 2003, a second innovation was introduced by commission agents from Kerala: A team of agents and their assistants would offer a price to growers based on the quality and grading of the apples; payment would be made on the spot through a local bank. It helped growers to receive immediate payment for apples sold at competitive prices. Although some sceptic growers worried about the prices offered, it was in the long?term interest of the commission agent to offer better than market prices: Knowing the quality of each lot they were acquiring, they could target them to the right market, thereby making more money than their competitors.

From 2004 onwards several newcomers made forays into apple marketing. Dev Bhumi Cold Chain Pvt Ltd, which owned cold stores in Delhi, bought apples and shipped them to Delhi in refrigerated vans. They tried several buying models and later built a controlled atmosphere facility in Matiana.

ITC Ltd made attractive offers for direct purchases from growers on whom they relied for quality control, but were disappointed by the poor quality supplied by many growers. There was talk about ITC working with a cold-chain fleet for transporting apples. In the second year they rented the grading-packing facility in Tikkar, owned by Himachal Pradesh Marketing Corporation (HPMC); ITC had to spend money to renovate the rundown facilities. Even though ITC understands marketing, they did not have the domain knowledge for apples, for which they unfortunately relied on several HP Government horticulture-related agencies; ITC ended its foray into marketing apples after the first year.

The most successful, pace-setting innovation in marketing is the one by Adani AgriFresh Ltd, which in 2006 set up three grading and CA storage facilities in Shimla District (Bithal, Rohru, and Sainj) in record time (Figure 4). Growers deliver apples in foam-lined plastic crates supplied by Adani, and after grading the payment is based on fruit quality, colour, and size. Adani directly ships second quality fruit to the mandis for immediate sale. The high-quality fruit stored in sealed controlled atmosphere facilities, is sent to the market in spring when apples fetch a much higher price. In the off season, Adani markets branded apples under the Farm-Pick brand. Several such CA facilities have now come up. In essence, such organizations act as consolidators – they buy directly from many farmers and consolidate the produce which they market under their own brands.

(Photo courtesy Adani AgriFresh Ltd.)

Many other organizations, such as Mother Dairy, the Reliance Group, and the Container Corporation of India also forayed into marketing apples.

Most remarkable is an initially small local effort that quickly shook up “Asia’s largest mandi” in Delhi: In 2004, a local farmer and a well-established commission agent opened a wholesale outlet (MKC Agro Fresh Limited) for apples in Narkanda (Figure 5). Its success in the first year resulted in similar ‘mini mandis‘ opening in nearby areas. Within a few years, this simple idea of bringing wholesale operations closer to growers – to which they can take smaller numbers of boxes, where they get paid within a few days, instead of having to go as far as Delhi to collect sales proceeds – forced all major commission agents from big cities to such mini-mandis to buy apple boxes in bulk for distribution throughout India.

Emerging Alternatives to the Arthi-Mandi System

All legacy (Royal, Rich-A-Red, Red, and Golden Delicious) apples are currently sold through the Aarthi-Mandi system. The chain from the grower to the consumer is long: It starts with the grower selling his produce to an Aarthi, at which point, in addition to transportation charges, he incurs three costs – selling fee (aarath) to the Aarthi, labour charges for moving apple boxes from the vehicle to the auction station, and a government fee. Then the auctioned cases are moved to the truck of the intermediate trader (Ladani), thereby incurring additional labour charges. It is not unusual for the apples to be resold several times to many intermediate Ladanis, each time adding the three costs outlined above. Thus, by the time the apples are sold to the final retailer, many additional costs accumulate. It is a cumbersome, inefficient system that cannot be reformed, especially by involving government agencies; it is on its way out. Royal Delicious apples in this mandi system fetch an orchard-averaged, wholesale price in the Rs 40-45 per kg range.

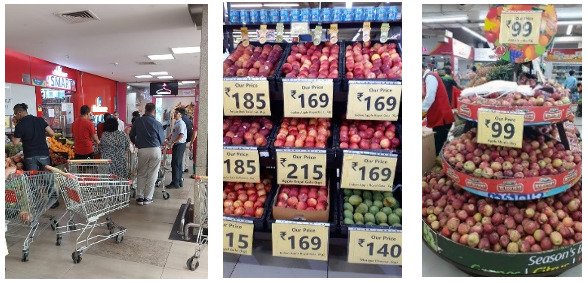

A parallel, more sophisticated, modern system is evolving rapidly that, in addition to selling most consumer items at attractive sites, also markets imported apples – which already have a larger volume than the apples grown in India. In contrast to the mandi system, these, and other rapidly evolving direct grower-to-retailer and grower-to-consumers companies – such as BigBasket and Reliance Retail – pay wholesale prices in the Rs 120-145 per kg range for new cultivars such as Red Delicious (SuperChief), Gala, and Fuji.

Initially, the BigBasket direct-to-customer (B2C) model focused on selling fruit via the internet: Customers place a direct order after seeing attractively advertised fruit on its website, which is quickly delivered to the customer. In this model return orders depend on the customer getting the high-quality fruit shown on the website, so that quality control is a critical part of the operation. To ensure good quality, all fruit is shipped to a central facility where the fruit is carefully checked before being repacked for customers (Figure 7). But the business now also sells in branded stores and directly supplies other businesses in a business-to-business (B2B) model.

for fruit quality. (Photos courtesy BigBasket.)

In contrast, Reliance Retail sells fruit directly in branded stores where the fruit is attractively displayed in clean, well-lit facilities. Here too, quality is important. However, for the customer – who in this model has to go to a store, where he can directly see the attractively displayed fruit he is going to buy – the risk of being disappointed is lower than for the internet-based model.

(Photos courtesy Reliance Retail.)

In competition with the CA stores, these companies have also started purchasing Royal Delicious apples: Depending on the market conditions, all of them offer Rs 65-75 per kg for the best quality apples. But the lower quality apples are offered much lower prices. Even for the best legacy apples, these prices are much lower than the Rs 120 per kg offered for the newer cultivars including the newer strains of Red Delicious, such as SuperChief.

Currently, not all the advantages of CA stores are being exploited: The time from which the apples are plucked to the time they enter the storage chambers easily varies from at least half a day to several days, during which time fruit metabolism lowers freshness. Fresh-fruit quality is best preserved when the plucked fruit is placed in chambers ‘immediately’ after being pre-chilled – necessary for rapidly lowering the fruit temperature. It will take time to adopt such best practices – but this will be required for Indian-grown new cultivars to compete with imported apples. And, of course, the use of reliable cold-chain transportation – now beginning to be used – will be critical for preserving fruit quality for eventual retail sale.

Essentially, companies such as BigBasket and Reliance Retail are acting as consolidators who buy produce from farmers and sell them under their own brand names. Because by directly selling to customers their marketing costs are lower than of Arthis, such companies will always offer better prices. While providing a means for getting better prices – especially for smaller growers – the brand identity of growers could be a casualty.

Direct Marketing Opportunities for Farmers

Recognizing the large spread between wholesale and retail prices, some entrepreneurs are experimenting with buying apples from farmers and selling them to retailers or, even better, directly to customers. Farmers could also do this: market apples by advertising them on the web, and then directly shipping them to customers via courier services (Grower to customer, or G2C). The high cost of courier services could be cut by transporting pre-labelled cartons to courier offices in cities, such as Delhi and Chandigarh, for efficient local delivery. The marketing of highly perishable cherries provides a viable model for this: Cherries packed in small punnets by growers are collected and brought to a central place from where they are transported overnight in small trucks to arrive in Delhi by 4:00 a.m. Metaphorically, in a manner similar to MKC bringing mandis from Delhi to local areas, this is equivalent to bringing the BigBasket model to growers.

Higher prices could also be fetched by packing several punnets, each with two to six apples, in a carton, for retail sale in punnets (Figure 8). Cartons with prelabelled punnets could be opened by courier services and locally distributed.

This courier-based, direct marketing model could substantially increase the income from very small holdings if growers change from common cultivars – such as Red Delicious, Gala, and Fuji – to the much higher priced apples such as Granny Smith, Jonagold, and Honeycrisp. In particular, Honeycrisp can sell at almost twice the price of Red Delicious apples. By focusing on quality, such small boutique operations could base their business on annual repeat orders from satisfied customers.

Dynamics of Apple Pricing

The Indian market for locally grown apples has four main sources: (1) The largest is from Kashmir, consisting of legacy apple varieties, mainly Royal Delicious, and other local varieties. Out-of-state entrepreneurs have leased large tracts of relatively flat land on which they have planted modern cultivars, such as Gala, in very large numbers on high-density root stocks such as M-9. In a few years Kashmir will flood the market with such cultivars to directly compete with imported apples. (2) Himachal Pradesh (HP) produces fewer apples than Kashmir, almost all of which, other than some early varieties, consist of Royal Delicious. Recently planted modern cultivars on high-density dwarf rootstocks will begin to yield marketable quantities in about five years. But, because of the much larger number of trees being planted in Kashmir, HP will lag behind in apple production. (3) The current output of Uttarakhand is much smaller. But, like Kashmir, that State is also pushing apple farming in a big way. Its growing output will provide additional competition within Indian grown apples. (4) Imported apples from abroad – mainly from the US and New Zealand, and potentially from Turkey and Iran – already exceed Indian production.

Currently, except for very small amounts of modern apple varieties, for practical purposes the Indian-grown apples mostly consist of legacy Red Delicious strains – such as Royal, Red, and Rich-A-Red Delicious – that mostly are sold through the Aarthi-Mandi system, which fetch orchard-averaged prices of about Rs 45 per kg. Following the lead of CA Stores, such as Adani Agri Fresh Ltd, newer companies, such as BigBasket and Reliance Retail have also started purchasing higher-quality Royal delicious apples for Rs 65-75 per kg.

The wholesale price of legacy apples, such as Royal Delicious, that mostly are sold through the Aarthi-Mandi system, fetch good prices just after the mango season ends, before the regular apple season starts, when even green-coloured apples are in demand. To enhance the colour of green apples, farmers spray them with ethephon that drastically reduces the shelf life of the apples and also damages the trees. The prices drop when, with the onset of the regular apple season, large supplies of apples become available. Road blockages during the monsoon can result in large accumulations in the Delhi mandi causing the prices to fall drastically. The prices are expected to improve somewhat during festive seasons, such as Diwali. The bottom line is that apple wholesale prices undergo very large fluctuations. Farmers attempt to send their produce when the prices are high – but this, at best, is a gamble. An alternative strategy is to put the apples in cold storage facilities – which are more suited for potatoes – and to sell the apples in spring when the prices increase. In cold stores the temperature is lowered but the atmosphere is not controlled. As a result the fruit shrinks/wrinkles.

Because of supply-and-demand considerations, prices of legacy apples are lower during bumper-crop years. In contrast, the wholesale prices of imported apples, as also of the newer cultivars grown in India, which are imported through cold-chain transportation and then stored in CA facilities, remain very stable throughout the year.

Already, more apples are imported than are grown in India. So, if there is an oversupply, then why do only the prices of Royal Delicious see large swings, while those of imported apples remain stable? What this indicates is that the overall market for the legacy apples – the bulk of which is consumed in rural markets – is limited. So, in effect, there are two broad markets: Legacy apples – mostly marketed through the Arthi-Mandi system – mainly cater to the cheaper, rural markets. While the newer varieties – marketed by the newer farmer-to-retailer or farmer-to consumer companies – cater to the more stable upscale urban markets. As these newer companies penetrate the rural market, the demand for legacy apples (Royal Delicious) will fall even further.

Normally, Kashmir-grown apples lag those grown in HP by a month: After Kashmir apples come into the market, the prices of the legacy apples drops even further. If this time lag also holds for the newer cultivars, such as Gala and Fuji, HP will have an advantage for about a month.

In the current mindset of apple growers the ideal apple is Royal Delicious (Red Delicious): This legacy apple has a dark red colour, an elongated shape, and the characteristic ‘bumps’ at the bottom – none of which have anything to do with the taste! Already, driven by taste, the latest versions of Red Delicious, such as SuperChief, are fetching lower prices than newer cultivars such as Gala, Fuji, and Honeycrisp. This price differential is expected to grow.

The Role of Packaging

Packaging serves two important functions: First, as a means for transporting apples from growers to the markets, for which the cartons must be designed to minimize damage. This is particularly important for apples with thin skins, such as McIntosh and Early Fuji, which are prone to surface damage. And second, smaller packages for direct retail, in the 1-5 kg range, for which aesthetic, attractive graphics are important. So far, the Indian apple industry has mainly focused on the larger cartons for transportation, which originally were wooden boxes designed to be transported by mules. They came in two sizes: A ‘full’ box weighing about 40 kg, and a 20 kg half-box. Later, the HP Government started manufacturing cardboard cartons in a government-run factory in Gumma, which produced ‘universal cartons’ of a fixed height in which the top could be closed by folding leaf extensions on the four sides. Using paper-mache trays for packaging, these cartons accommodated four layers of extra-large apples; five layers of large, medium and small apples; and six layers of extra-small and extra-extra small apples. These universal cartons have the advantage that they cannot accommodate extra layers, thereby restricting the overall weight to about 23.5 kg (net fruit weight of about 22.5 kg). Of course, higher weights result from overfilling – such as by filling large apples in trays designed for medium apples.

Later telescopic cartons, in which a top half is placed on the lower half, were introduced. When used properly, with the same layer counts as in the universal carton, they result in the same weights as in the universal carton. The advantage is that for some grades, slight extensions above the top can be accommodated by the top resting on the top-most layer of apples instead of the top seating on the rim of the bottom half of the carton. Depending on the size grade, the net fruit weight in full (5-layered) – and half-size (2-layered) cartons is about 22.5 and 9 kg, respectively – about 4.5 kg per layer.

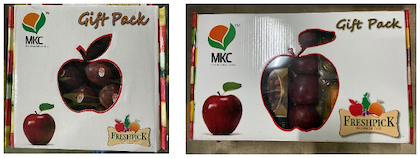

Special clear-plastic or paper punnets (small containers) for direct retail sales of 2 to 10 apples are being used for internet-based and direct sales in upscale stores (Figure 9). Gift packs in smaller cardboard boxes are also being used (Figure 10).

(Photo courtesy of MKC.)

Given the poor road conditions, much work needs to be done to improve the design of cartons to prevent mechanical damage to apples – the existing carton designs leave much to be desired – specially to compete with the almost damage-free quality of imported apples.

Concluding Remarks

Replacing Royal apples with modern cultivars, and shifting to the rapidly evolving modern marketing channels, offer the best hope for the future of the Indian apple industry. The primary job of growers should be to produce the best-quality apples possible; those that the customers want – such as Gala, Fuji, and Honeycrisp – and delivering them to customers in fresh, undamaged condition, which will require a significant improvement in carton design.

Growers must move away from the Royal Delicious and ‘Washington Apples’ (essentially Super Chief) mindset, and grow the newer, higher priced cultivars such as Gala, Fuji, Jonagold, Honeycrisp, and Granny Smith. Other headwinds for the apple industry include the effect of climate change on apple growing. In addition to anti hail nets, it may become necessary to provide shade to protect apples from the increasing temperatures. Only then will they be able to compete with, and fetch the better prices of, imported apples that already account for more apples than are produced in India.

To emphasize the impact of rapidly changing technology on marketing of apples, this article started with the example of how horse-driven carriages were rapidly replaced by automobiles – without any intervention by the government. Now, because of the imperative of climate change, and the development efficient batteries, the petrol- and diesel-driven automobiles will rapidly transition to non-polluting, electric vehicles. This will eliminate the jobs of the very large body of people presently employed in maintaining and repairing engine-driven vehicles. In a similar manner, the very rapid changes occurring in all aspects of life will require the apple industry to rapidly respond to such changes. It is wishful thinking to depend on the very slowly moving government agencies for solutions to growers’ problems: Growers must outgrow self-defeating practices such as overfilling cartons that damage apples. And, to survive – through proper tree pruning, and plant protection and plant nutrition practices – they must focus on significantly improving the quality of apples to meet international standards.

Vijay Kumar Stokes, PhD (Princeton, 1963), taught at IIT Kanpur (1964-1978), where he headed the Mechanical Engineering Department (1974-1977) and was the Convener of the Nuclear Engineering and Technology Program (1977-1978). He then worked at the GE Corporate R&D (1978-2002). Besides setting up a world-class, science-based apple orchard at his ancestral home in Ilaqa Kotgarh, for over 25 years he has been documenting the local language, culture, and music and dance.

Very objective & scientific analysis of reforming apple production & apple marketing to compete with international apple growers.

Still a long way to go for apple growers in HP, as their mindset & perception is stuck in deep rooted unscientific methods of production & marketing & covered with multiple layers of a centuries old methodology of apple growing & marketing, which will have to be reformed first.

So the change will have to start first within the minds of the growers first & not from the outside.

Full marks to you, Dr. Vijay Kumar Stokes.

This article is an insightful exploration of the changing landscape in India’s apple market. The historical context of the mandi system, so thoroughly detailed, serves as a perfect backdrop to the real need for reform. It skillfully captures the dilemma of farmers relying on outdated methods like the arthi-mandi system, which may once have been useful but is now a roadblock to progress. The analysis of premium varieties such as Gala and Fuji emphasizes how modern markets are shifting not just toward taste, but toward survival and better profitability.

A personal reflection comes to mind here. Growing up, I remember the bigger the apple box, the better we thought our chances were of fetching higher prices. We would carefully pack the largest, most perfect apples on top, but those poor apples were probably the first to face the music as explained in the article. And talking about music—what a performance the chowdris gave, stomping on the boxes like they were dancing in a Bollywood number, shoving them into trucks! Ironically, we’d get a scolding for handling an apple too roughly, while the chowdris were doing their “dance” on the boxes.

The thought-provoking aspect of this article is the focus on the grower-to-consumer model. While it’s undeniably the future, there are practical challenges that come with it. It’s not as simple as bypassing the mandi; the logistical complexity of delivering fresh, undamaged apples to consumers directly requires more than just good intentions. For many small-scale farmers, the infrastructure isn’t quite there yet. Can this model be scaled in a way that includes all growers, without compromising on quality or profit?

Mr Stokes’ research and depth of understanding are commendable, and the article raises critical questions about the future of apple marketing. By emphasizing the need for smarter, modern approaches, it leaves the reader thinking about how we can overcome these practical barriers and truly step into the future.