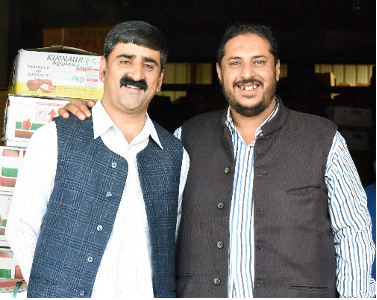

Ilaqa Kotgarh, about 80 km from Shimla on the old Hindustan-Tibet Road, where the first Delicious variety of apples was introduced by Samuel Evans Stokes about a century back (1916), does not now produce the most apples in Himachal Pradesh, nor is it the richest. But it continues a surprising tradition of innovation concerning all aspects of apples. For example, in 2004, in collaboration with Haji Shadab, a well-established commission agent from Ghaziabad, Kuldeep Mehta from village Thinu opened a wholesale outlet (MKC Agro Fresh Limited) for apples in Narkanda, about 18 km from Kotgarh. It had surprising success in its very first year, resulting in similar ‘mini mandis’ opening in nearby areas.

mini-mandis close to apple growers.

Within a few years, this simple idea of bringing wholesale operations close to growers – to which growers can bring smaller numbers of boxes, where they get paid within a few days, instead of having to go as far as Delhi to collect sales proceeds – forced all major commission agents from big cities to come to such mini-mandis to buy apple boxes in bulk for distribution throughout India. It caused a major disruption in ‘Asia’s largest’ wholesale fruit market in Delhi: Instead of almost all apples being shipped to Delhi for onward distribution, major wholesalers now come to mini-mandis near the farmers. In contrast to this innovation, Government agencies continue to think of making larger and larger centralized mandis.

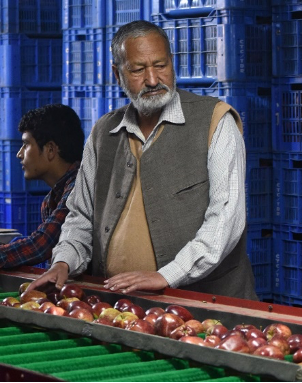

Similarly, although apple grading machines had been in use in several orchards for some time, in 2006 Chet Ram Chauhan started the first commercial apple grading operation near his village of Bankoti: small growers brought their apples to his grading machine in plastic crates supplied by him, where local apples were graded and packed, ready to be shipped in trucks. In its very second year this operation graded apples brought all the way from Kinnaur. Within a few years such commercial grading operations have mushroomed throughout Himachal’s apple growing belt.

apple grading.

In October 2016, people of Ilaqa Kotgarh gathered in Thanedhar to celebrate the Centennial of the arrival of the Delicious variety of apples to our area. It was a good platform to review the history of our Ilaqa, and to take stock of where we have come from – the reasons for the continuing innovations in the apple industry – where we are, and what the future may hold.

Way, way back we were under the Rana of Kotkhai who – because we were an unruly, uncontrollable lot – asked the Raja of Kullu to administer us. But after paying revenue to Kotkahi for a few years, he annexed the Ilaqa into Kullu, under which we continued for 10 years. Then, in a ‘war’ between the states of Kullu and Bushahr, the Raja of Kullu was killed. In exchange for his body, we were ceded to Bushahr, under which we were for 40 years.

As a part of the conquest by the Gorkhas, all the nearby princely states, including Bushahr were sacked and all records destroyed. This occurred in the 1806-1811 time-frame. Because the weak, self-indulgent princelings and rajas of the Hill States were no match for the warlike Gorkhas, they approached the British for help. The British obliged and in collaboration with the local ‘armies’ defeated the Gorkhas in 1815.

The British rewarded those who had stood by them by returning the lands to the original rulers, but also burdened them with British Political Agents to oversee orderly governance. While Kulu and Bushahr were squabbling for the rights to our Ilaqa, the British decided that they needed a presence to stabilize the region and ended up incorporating Ilaqa Kotgarh into British Panjab, and to maintain order they stationed soldiers in Kotgarh from 1815 to 1843.

So, what we now know as Ilaqa Kotgarh was ‘born’ in 1815; we should have celebrated its Bicentennial in 2015! This annexation by the British affected our future in three ways: (1) As long as the laws were obeyed, we were not oppressed as in the surrounding states, and we were free to express our thoughts. (2) The Ilaqa was dry, and remained dry till the early 1980’s when one of the HP Chief Ministers from a former princely state opened it to liquor vends. And, (3) formal education in our Ilaqa began with the establishment of the Gorton Mission School in Kotgarh in 1843, which gave our Ilaqa a head start in education. Of course, there was a downside to this annexation by the British; they introduced the Begar system that required the local people to provide free produce and labour to visiting government functionaries. This blot was later abolished by the efforts of Stokes after he became actively involved in India’s freedom struggle.

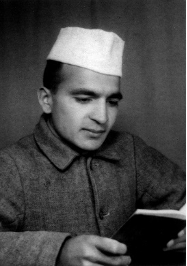

The Ilaqa became 100 years old in 1915. The first Delicious variety apples were brought to our Ilaqa in 1916 by SE Stokes, who came to India from the US in 1904 at age 22, and purchased a large tract of land in 1912, and started building his now 110-year old house, Harmony Hall, in 1912.

After working in Gorton Mission School, Stokes started a primary school in Naini Dhaar. He then started the Tara School in Barobagh, where students were also taught declamation and music, and learned apple growing by working after school in his new orchard. Later he also played a leading role in keeping alive the newly started school in Dhada, now Vir Garh, which almost closed several times, as late as in 1938. Later, Ram Dayal Singha was to play an important role in the rejuvenation of this school.

of apples to Ilaqa Kotgarh.

In the 1920s, Ilaqa Kotgarh became better known in India because of Stokes’ intense involvement in the Indian freedom struggle, in which he worked with the likes of Gandhiji and Lala Lajpat Rai. In 1921 he spent six months in Lahore Jail on sedition charges. Many educated locals later joined him in his quest for order and justice.

Education, the rule of law allowing one to think and comment on issues of the day, and the exposure of locals to India’s freedom movement – unique to Ilaqa Kotgarh because of its history – is most likely the reason for the continuing innovation in apples in Ilaqa Kotgarh.

Although the very limited number of apple orchards had started to produce commercial quantities of delicious apples in the 1930s, the produce had to be transported on mules. The British made the first motorable road to Narkanda in the early 1940s to get access to hard wood for gun buts; later a narrow road opened up to Thanedhar.

The substantial increase in apple prices in the 1950s from the ban on Australian apples led to the second, large wave of apple plantation; there were almost no apple trees in the surrounding villages in 1960 – by 1970 planted trees were about 4 feet high.

The first commercial apple nurseries were started by Lakshmi Singh Sirkeck and Lal Chand Sirkeck. They supplied trees for subsequent apple plantations in Kotkhai.

first apple tree nursery in the 1940s.

In 1937, Kedar Nath Chauhan started the first Diesel-engine-run saw mill for making apple boxes; the disassembled engine parts were transported from Shimla to Dokhri, near Thanedhar, on the backs of Kashmiri porters! His example was copied all over the State till the use of wood became untenable; in 1989 the HP Government set up a corrugated paper apple carton plant in Gumma.

sawmill for making wooden boxes for apples in 1937.

Innovation continued: In 1980 Uma Paul of Dabbi set up the first pre-nursery school in village Suld, where she taught English, Hindi, and Mathematics. Later she moved the school to Dabbi; it became a great success and gave students an early start to excel. This led to the mushrooming of many local English-medium schools.

Apples brought ‘instant’ unheard of prosperity to people at the higher altitudes. The downside of this was that jobs were not considered important, so why study. People from the lower altitudes, such as from Kanda and Kirti, and to some extent from Dalan, where apples do not grow easily, went into service for which education was important. The easy money and lack of education at higher altitudes resulted in people not understanding the scientific foundations of apple growing. So, among other factors, poor pruning practices have resulted in very poor productivity. In Himachal, on an average, we produce 5-10 times less apples per hectare than the international norm! The HP Government has mainly been a passive, blind observer.

But someone did worry: Hari Roach from village Saroga became very passionate about apple cultivation. In 2000, he imported clonal dwarf rootstocks from the US, and in 2002 he organized the effort to the import modern cultivars on clonal rootstocks from the US.

apple varieties on dwarf rootstocks.

Besides adding to the efficiency of apple packaging, selling, and transportation, these innovations have generated local jobs. Our reputation has attracted outside innovators to our Ilaqa: In 2006, Adani Agrifresh Ltd set up the first Controlled Atmosphere facility for apples in Bithal, allowing apples to be stored with very little deterioration. And in 2012, the innovative couple of Kartik and Anuradha Budhraja started Kotgarh Fruit Bageecha Pvt Ltd in Shathla village for making boutique jams and chutneys from locally sourced fruits.

So, as things stand, many changes are occurring in apple growing, packaging, storage, transportation, and marketing. But the rejuvenation of apple orchards with modern varieties on more productive dwarf rootstocks is just catching on. We are way behind the main apple growing regions of the world that have access to the latest technologies that our government is incapable of providing. And we do not have viable holdings to make use of economies of scale.

Now that the Ilaqa is 200 years old, and we have had apples for 100 years, what challenges face us next?

Even if we are able to produce world-class apples, we will find it difficult to compete on price with imported apples that are mostly grown on relatively flat terrains where growing trees, plant protection and nutrition, and harvesting can be mechanized. In contrast, because of climatic conditions in India apples can only be grown in hilly terrains at high altitudes, where mechanization is not feasible; labour-intensive harvesting depends on migrant labour from Nepal. And all the inputs have to be transported from the plains. Most imported apples, which are harvested about six months before arriving in India in controlled-atmosphere containers, do not keep well after release into the retail market. In contrast, tree-fresh local apples can be transported to retail stores in refrigerated trucks to all parts of India within a week. The superior taste of tree-fresh apples offers the only advantage over imported apples.

As an alternative, smaller holdings can be used for the huge, burgeoning eco-tourism sector – bed-and-breakfasts, trekking, … – for which the beauty of the mountains provide an attractive setting, both during summers and for winter sports.

But the real future lies in the emerging knowledge-based economy that requires high-quality education: The world is changing at an exponential rate, as a result of which what we learn today may not be relevant in a few days. How do we prepare for this rapid change? Clearly, this will require quality education that focuses on training the mind to think – the essence of education – rather than the current curricula that emphasizes cramming large amounts of information that is easily accessible through the many digital platforms that people now have access to.

Our government school systems run by a snail-paced education board is incapable of responding to such changes – any new curriculum is outdated the very day it is introduced. Owing to political pressures, more and more inadequately-staffed schools are being opened that mostly focus on non-science oriented curricula. At the very least, science must be emphasized. And the current quantity driven focus must move towards quality.

Vijay Kumar Stokes, PhD (Princeton, 1963), taught at IIT Kanpur (1964-1978), where he headed the Mechanical Engineering Department (1974-1977) and was the Convener of the Nuclear Engineering and Technology Program (1977-1978). He then worked at the GE Corporate R&D (1978-2002). Besides setting up a world-class, science-based apple orchard at his ancestral home in Ilaqa Kotgarh, for over 25 years he has been documenting the local language, culture, and music and dance.

Well documented post of the History of Ilaqa Kotgarh. Its written well in sequence and writer hv justified the local Ilaqa ppls contribution.

This post/ writeup ll definitely help the researchers for further research of Ilaqa.

Well written Sir ??

Excellent work and wonderful research work sir. It will definitely help many researchers in this field.

Tara high school was the alma mater of my grandfather. He always spoke highly of the education and curriculum, and still appreciates the impact it had on him.

Thank you very much for the article, Sir.

I fully agree with you that, “Education, the rule of law allowing one to think and comment on issues of the day, and the exposure of locals to India’s freedom movement – unique to Ilaqa Kotgarh because of its history – is most likely the reason for the continuing innovation in apples in Ilaqa Kotgarh.”

You are quite right that “Clearly, this will require quality education that focuses on training the mind to think – the essence of education – rather than the current curricula that emphasizes cramming large amounts of information that is easily accessible through the many digital platforms that people now have access to.”

Lovely article ? thanks for such a post

The article is both well-researched and packed with information, diving deep into the innovations that are reshaping our apple economy and the challenges that lie ahead. Big kudos to you Sir, for such a rich, comprehensive overview!

While it correctly points out that producing world-class apples in our hilly terrains will always be more labor-intensive and less mechanized than in flatland competitors, I think there’s an intriguing twist worth considering. With climate change accelerating, areas that once had perfect growing conditions might face their own set of challenges — potentially levelling the playing field. Could our rugged, hilly terrain, which might naturally resist some of these shifts, become a hidden advantage in the long run? Or maybe I’m just overestimating our odds… or underestimating the world’s mess!

Overall, this article left me with plenty to ponder. It got me thinking — maybe the future of apple farming (and everything else) isn’t just about how we work the land but how we cultivate our minds. 🌱

It’s a must-read for anyone interested in the future of our region, its apples, and much more!